This post was written by Lana Mason, Processing Student Assistant. Lana has an Associate of Arts degree in Fine Arts from Piedmont Virginia Community College. She is currently studying Art History at George Mason University. Lana was the recipient of the University Libraries Student Assistant Scholarship for the 2018-19 academic year.

This is the second post in a six-part blog series exploring the campus culture of George Mason University through the lens of each of its six past presidents’ tenures. The materials referenced in these posts are derived from the George Mason University Office of the President records (hyperlinked).

On April 3, 1973, the Board of Visitors named Vergil H. Dykstra the second president of George Mason University (GMU). Dykstra was comparatively young—only 48 years old—and held a PhD in philosophy from the University of Wisconsin, one of several universities at which he had held teaching positions. In addition to his educational experience, he was an appealing candidate to become president of the newly minted university due to his administrative background. From 1962-1964 he was Associate Dean of Harpur College in New York, and became its Vice President for five years following when Harpur College became the State University of New York at Binghamton. His experience of overseeing the transition of a college to university in a major administrative role suggested to the Board that he would be able to contribute to the same kind of success at GMU.

Dykstra became president at a formative time in the university’s life. He oversaw a rapid expansion of the student body (growing 28% in a single year)[i] and major campus development projects including new buildings and land purchases. During his administration, the university launched multiple new academic programs, and laid the groundwork for the eventual development of the School of Law.

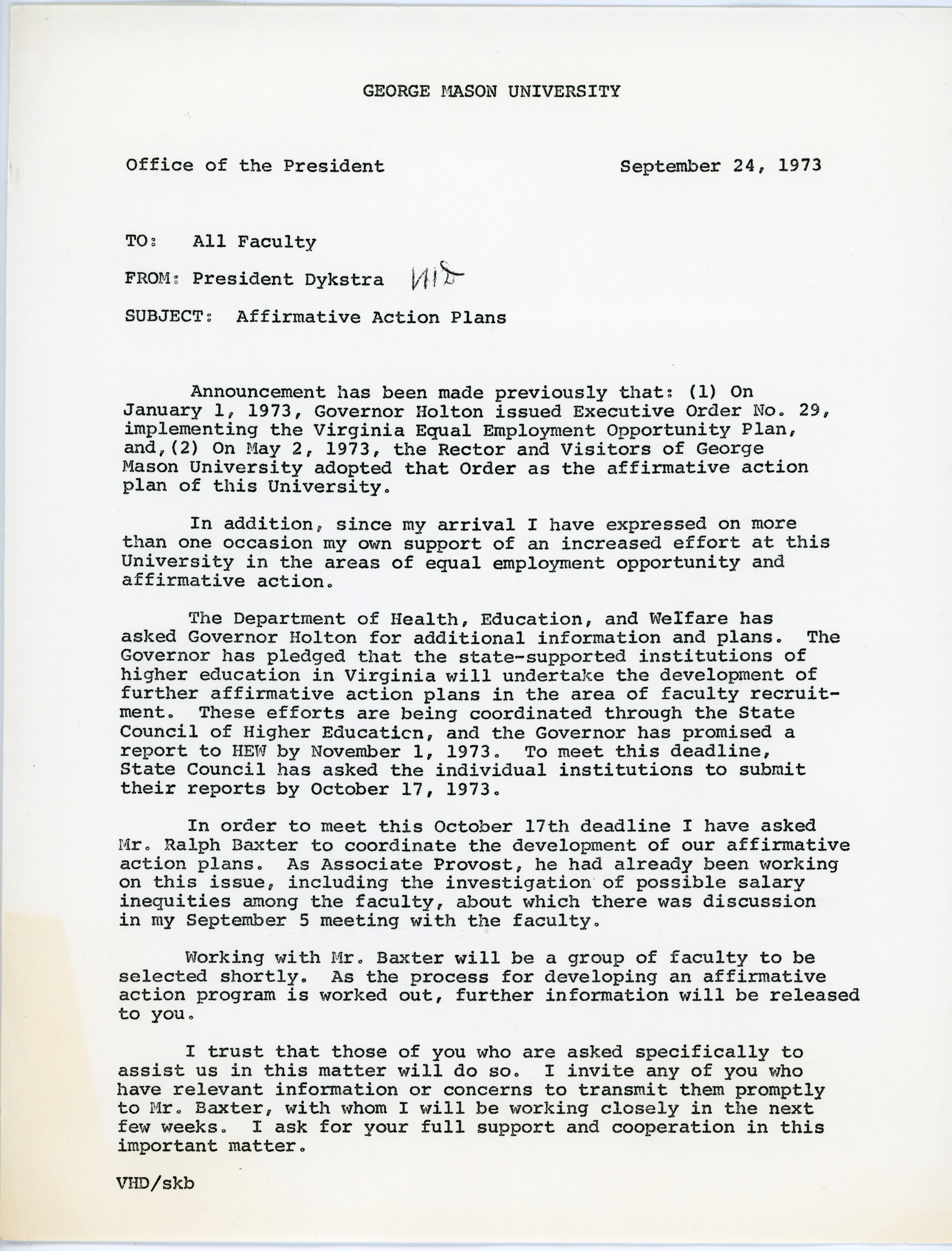

During the 1970s, Virginia finally confronted its long-term issues with fighting racial integration in higher education. Affirmative action programs became a major focus (and often point of contention as well) at many institutions, including GMU. Affirmative action, while primarily intended to encourage racial diversity in both the student body and faculty, also helped bring women’s pay equity and employment to the forefront of administrative consideration.

As discussed in part 1 of this blog series, GMU was in its early years a very racially homogenous school, with 98.3% of freshman students in the 1960s identifying as Caucasian.[ii] Racial diversity among faculty at the school was only slightly better, with only 8.5% of all faculty identifying as non-white.[iii] As part of the GMU Affirmative Action Plan to promote diversity and equity, Dykstra developed the Council on Minority Relations and an Affirmative Action Task Force. One of the primary efforts of these groups was to promote recruitment of students of color and improve accessibility of the faculty hiring process. Dykstra was a strong advocate of fostering diversity and fairness at the school—he regularly voiced his support of “equal employment opportunity and affirmative action”[iv] and worked to establish organizational change to support these objectives.

While Dykstra concentrated much of his administrative efforts into improving equity at Mason, he took a somewhat oppositional stance towards another issue of great concern to the university—student housing. Despite transitioning to an independent university in 1972, the school had never constructed on-campus housing for its student body. Dykstra advocated for keeping housing to a minimum, suggesting that while it was necessary to have some type of housing, student dormitories were the least preferred method of accomplishing that due to the cost and the impact on school culture. [v] Despite his reservations, on-campus student dormitories were a priority to many administrators and students alike, and the first student apartments began to be constructed near the end of Dykstra’s tenure.

In April 1977, after four years as president, Dykstra left George Mason University. Robert C. Krug, then the Vice President of Academic Affairs, was quickly appointed as acting president of the university to fill Dykstra’s empty shoes. He would go on to be GMU’s third president for one year, with a much longer-serving president following in his and Dykstra’s footsteps.

[i] “Office of the President Report,” December 9, 1975, George Mason University Office of the President records, R0019, series 4, 2.10, Special Collections Research Center, George Mason University Libraries.

[ii] See https://vault217.gmu.edu/?p=8812 for more information.

[iii] “Minority faculty at George Mason University (Fall 1973),” March 12, 1974, George Mason University Office of the President records, R0019, series 4, 2.10, Special Collections Research Center, George Mason University Libraries.

[iv] “Affirmative Action Plans,”September 24, 1973, George Mason University Office of the President records, R0019, series 4, 2.10, Special Collections Research Center, George Mason University Libraries.

[v] “Letter to Board of Supervisors,” February 18, 1974, George Mason University Office of the President records, R0019, series 4, 3.9, Special Collections Research Center, George Mason University Libraries.

Follow Special Collections Research Center on Social Media at our Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter accounts. To search the collections held at Special Collections Research Center, go to our website and browse the finding aids by subject or title. You may also e-mail us at speccoll@gmu.edu or call 703-993-2220 if you would like to schedule an appointment, request materials, or if you have questions. Appointments are not necessary to request and view collections.