To many 21st century Americans, opera might conjure images of women in horned helmets belting out screechy songs in incomprehensible languages., and shattering panes of glass in the process. This stereotype has its origins in the German composer Richard Wagner’s operas with stories based in Norse mythology, and it is an exaggeration of only a small fraction of the operatic output of over 400 years. Opera is significantly more diverse, accessible, dramatic, and downright beautiful than the stereotype suggests – it is an art form that portrays a wide range of human emotion and experience, and the items in the opera case in SCRC’s “ ‘Showing Us Our Own Face:’ Performing Arts and the Human Experience” exhibit were chosen to reflect some of the depth and breadth of the discipline.

One of the items in the case is a poster from a production of George Frideric Handel’s opera Rinaldo, staged in Halle, East Germany (Handel’s hometown) in the 1980s. Handel wrote the opera in the 18th century, and at the time, the star singers of the opera world were castrati (singular: castrato). Castrati were adult men who sang in the upper vocal range equivalent to modern female mezzo-soprano and soprano singers, and were able to sing like this because they had been castrated before their voices changed at puberty. Essentially, castrati kept the vocal range of young boys. For obvious reasons, this practice died out and adult male tenors and female sopranos became the preferred voices for main opera roles in the 19th century and beyond.

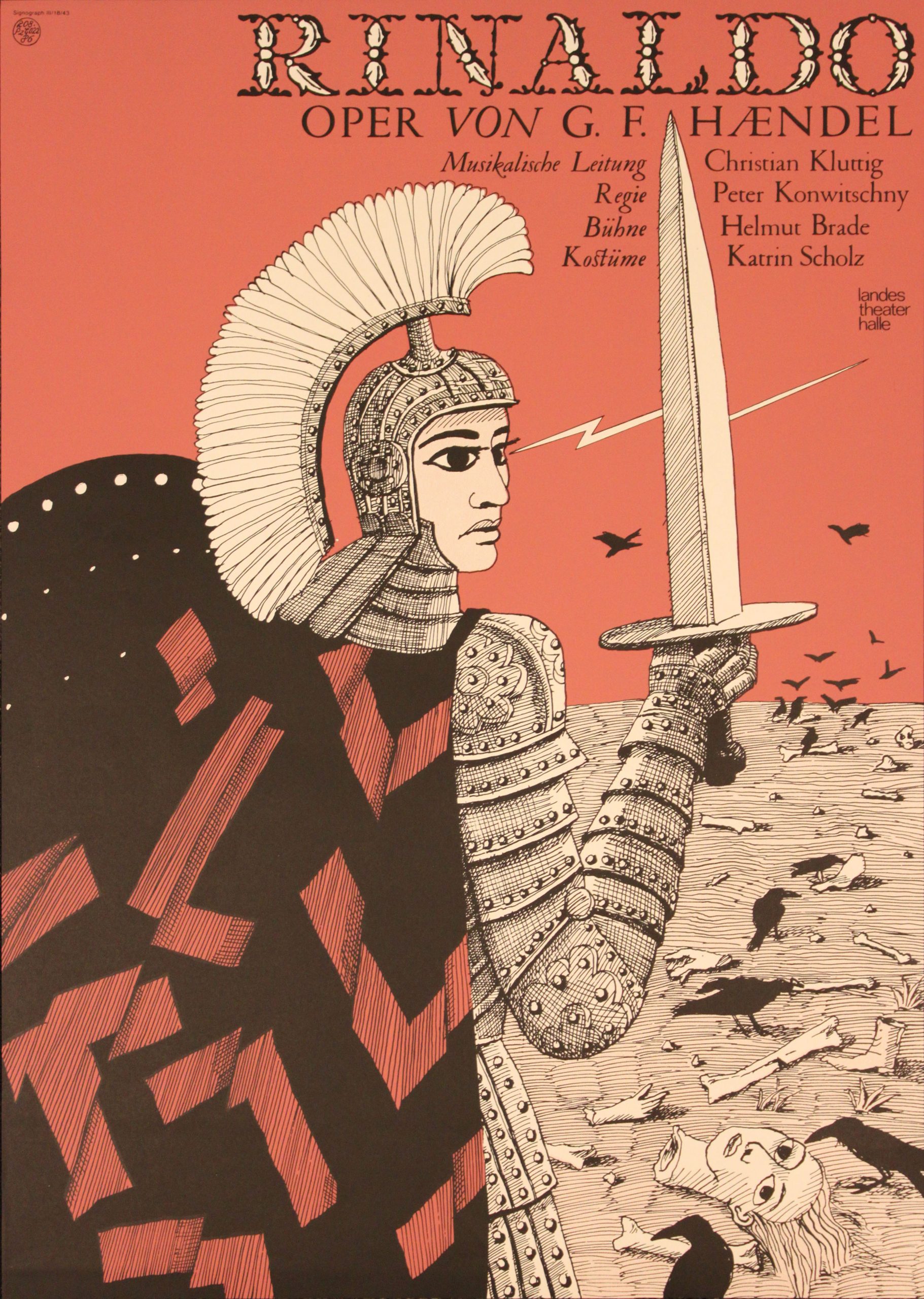

The poster advertising Handel’s Rinaldo in SCRC’s exhibit, circa 1980s. East German poster collection performing arts series, C0209, PA-0144, Special Collections Research Center, George Mason University Libraries.

In the 20th and 21st centuries, when opera companies stage 18th century Baroque operas that have leading roles written for castrati, they have two main options – cast a female mezzo-soprano in the part, or give the role to an adult male countertenor, a voice part that requires men to use falsetto to sing in a higher range. The first option in particular provides directors with an opportunity to play with ideas about gender and fluidity in a way that is extremely relevant to the modern world. As an example from SCRC’s exhibit, the poster for Rinaldo depicts the title character, a role written for a castrato, in full armor on a battlefield, but with traditionally “feminine” lined eyes and features.

Another more recent production of another Handel opera, Giulio Cesare, starred mezzo-soprano Sarah Connolly as Roman general Julius Caesar – see Barry Millington’s review in the Evening Standard for photos from a revival of the production. Casting women in these martial roles allows the audience to question power and its relationship to traditional “masculinity,” and it challenges gender stereotypes in a strikingly modern way for 18th century art.

There are many other pieces in SCRC’s “Showing Us Our Own Face” exhibit, in the opera case and in others, that demonstrate that the performing arts can challenge our views of society and reflect a broad spectrum of the human experience.

“Showing Us Our Own Face”: Performing Arts and the Human Experience will be on display until May 2020 in Fenwick Library, 2FL.

Follow SCRC on Social Media and look out for future posts in our Travel Series on our Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter accounts. To search the collections held at Special Collections Research Center, go to our website and browse the finding aids by subject or title. You may also e-mail us at speccoll@gmu.edu or call 703-993-2220 if you would like to schedule an appointment, request materials, or if you have questions. Appointments are not necessary to request and view collections.