As we come to the end of our blog series related to SCRC’s spring 2020 exhibit “Showing Us Our Own Face: Performing Arts and the Human Experience,” it is impossible not to reflect on the way that performance and the performing arts world have changed due to COVID-19. When my colleagues and I were creating the exhibit in the late fall and winter of 2019-2020, we could not have imagined a time when theaters, concert halls, and other performance venues were closed for months with no definitive end in sight. None of the disciplines highlighted in the exhibit have escaped the ravages of the pandemic on the human ability to gather and share the joy of live performance and creation, and music, the subject of one of the cases (and this blog post) is no exception.

I myself have been a choral singer since the age of 7 (with occasional breaks of a few years), and my most formative musical experiences were as part of a group, learning to breathe and blend as part of an ensemble. I imagine that those who play in bands and orchestras and are used to the incomparable bonds created between musicians as they perform together must feel the same sense of sorrow at being cut off from this source of communion. Instrumentalists and singers can certainly perform alone, and many have been sharing their talents virtually via Youtube and other social media platforms. However, there is simply no replacement for performing together in person – as we are all learning, technology only goes so far.

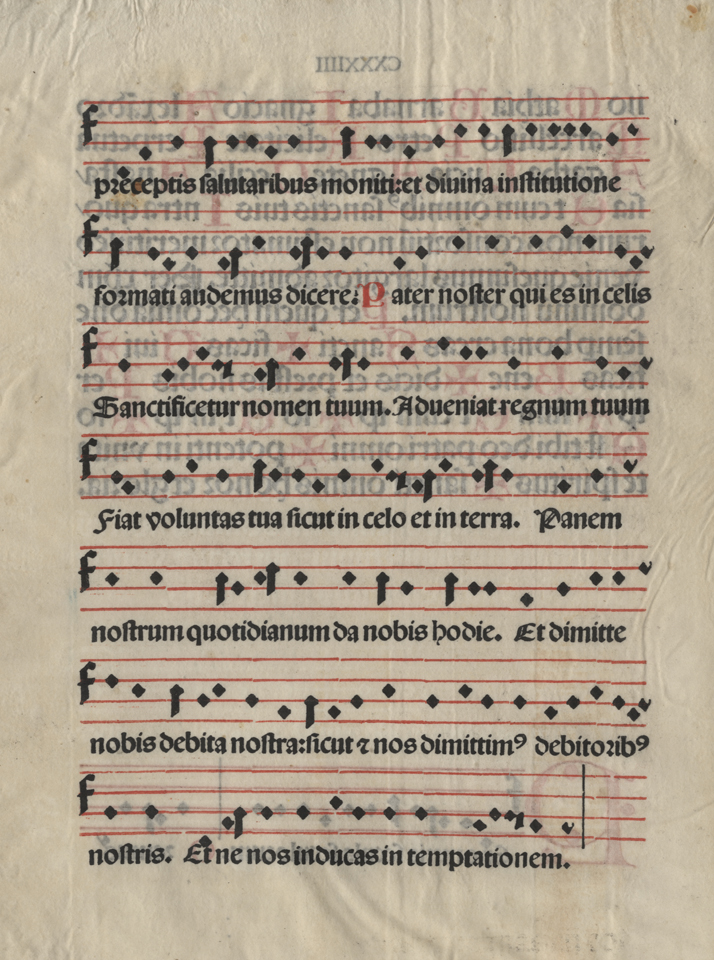

Several of the items in the exhibit’s music case are a testament to the ensemble nature of music-making through the ages. For example, the Pater Noster (“Our Father” in Latin) Gregorian chant in the Missale Brixinense from 1493 is meant to be sung as an act of collective worship as part of Mass:

The effect of multiple voices singing a unison line of chant provides a unity among the choir, congregation, and clergy that is impossible to achieve without music.

Another item in the exhibit’s music case, the post-Civil War collection Slave Songs of the United States, speaks to music’s presence and power even when human lives have been stolen. Enslaved people, who were so often permanently torn asunder from those they loved, expressed themselves and created community through music. There is of course not even a hint of comparison between our temporary COVID-19 situation and the horrors of the American system of slavery and its centuries of ramifications, but these songs speak to the power of music beyond all other art forms to endure and connect us in our humanity.

I have no answers to make our current situation any easier, other than, as so many have already said, virtually embracing the release that music has always brought in difficult times. The German composer Franz Schubert expressed this effect to perfection in his lied (a German art song) “An die Musik,” and I can think of no more fitting way to end this post than with this song performed by the great English Mezzo-Soprano Dame Janet Baker:

“Showing Us Our Own Face”: Performing Arts and the Human Experience will be on display until May 2020 in Fenwick Library, 2FL. This is the last post in a series of posts highlighting the exhibit.

Featured image citation: Bifolium from the Missale Brixinense with the Lord’s Prayer in Gothic musical notation, 1493, BX2015 .A2 1493, Special Collections Research Center, George Mason University Libraries

Follow SCRC on Social Media and look out for future posts in our Travel Series on our Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter accounts. To search the collections held at Special Collections Research Center, go to our website and browse the finding aids by subject or title. You may also e-mail us at speccoll@gmu.edu or call 703-993-2220 if you would like to schedule an appointment, request materials, or if you have questions. Appointments are not necessary to request and view collections.