This blog was expanded from text in SCRC’s Spring Exhibition “Showing Us Our Own Face”: Performing Arts and the Human Experience.

In mid-century America, you would be hard-pressed to find two dancers more popular than Martha Graham and Maria Tallchief. Both masters of their respective arts, the two women were trailblazers in the world of dance.

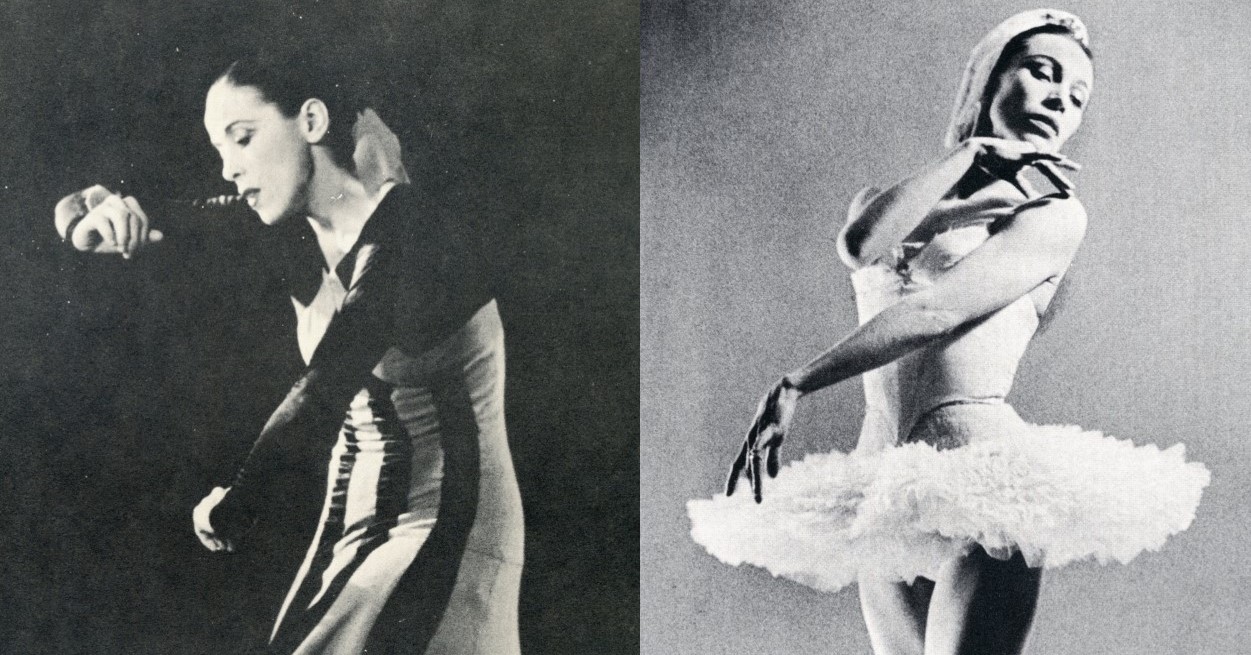

Maria Tallchief. New York City Ballet 1959-1960 season program, 1959. Charles Rodrigues playbill collection, C0184, Box 27, Folder 2

Special Collections Research Center, George Mason University libraries.

Martha Graham. Playbill for a performance by modern dancer Martha Graham, 1958. Mary Lavigne programs collection, 2020.009 Special Collections Research Center, George Mason University libraries.

Expressing emotion and narrative through movement of the body, or dance, is present in just about every culture on the planet, both in codified and non-codified ways. Codified dance, ballet being the most well-known, has risen to the rank of high art, with dancers dedicating their lives to perfecting the art form. With the advent of the 20th century, dance began to evolve beyond codification. Isadora Duncan was a pioneering dancer who rejected technique in favor of freedom of the body, as well as freedom of expression. She is often regarded as the creator of modern dance, which is the yin to ballet’s yang. Duncan paved the way for others to reject the ballet model, and introduce other modes of dance into the mainstream. Martha Graham was one such dancer, who continued to break barriers in Duncan’s wake, and arguably surpassed her in renown.

Martha Graham dancing, photographed by Barbara Morgan. Image Source.

Born in 1894, Graham pioneered her very own dance style, known as the Graham technique. According to the Martha Graham Dance Company’s website: “Graham created 181 ballets and a dance technique that has been compared to ballet in its scope and magnitude. Her approach to dance and theater revolutionized the art form and her innovative physical vocabulary has irrevocably influenced dance worldwide.

“In 1926, Martha Graham founded her dance company and school, living and working out of a tiny Carnegie Hall studio in midtown Manhattan. In developing her technique, Martha Graham experimented endlessly with basic human movement, beginning with the most elemental movements of contraction and release. Using these principles as the foundation for her technique, she built a vocabulary of movement that would ‘increase the emotional activity of the dancer’s body.’ Martha Graham’s dancing and choreography exposed the depths of human emotion through movements that were sharp, angular, jagged, and direct.” Graham danced well into her seventies, and choreographed into her nineties. She died in 1991 at the age of 96.

…

Maria Tallchief was one of the most striking and talented ballet dancers of the 20th century, and was considered the most famous prima ballerina in mid-century America. Tallchief was of Osage and Scots-Irish descent, marking her the first Native American ballet dancer to reach such renown. However, it was Maria herself who said “Above all, I wanted to be appreciated as a prima ballerina who happened to be a Native American, never as someone who was an American Indian ballerina.” Tallchief found a creative home for three decades with the New York City Ballet, and collaborated to much success with its founder and choreographer George Balanchine. The lead role in Balanchine’s version of the ballet The Firebird was created for Tallchief, who was known for her perfect technique, as well as her intense passion and athleticism when dancing. In her New York Times obituary, her colleague Jacques D’Amboise, “who was a 15-year-old corps dancer in Balanchine’s ‘Firebird’ before becoming one of City Ballet’s stars, compared Ms. Tallchief to two of the century’s greatest ballerinas: Galina Ulanova of the Soviet Union and Margot Fonteyn of Great Britain.

Maria Tallchief dancing in Firebird costume. Image source.

“‘When you thought of Russian ballet, it was Ulanova,’ he said an interview on Friday. ‘With English ballet, it was Fonteyn. For American ballet, it was Tallchief. She was grand in the grandest way.’” Tallchief would go on to found the Chicago City Ballet in 1981, and continued performing and teaching ballet until her death in 2013.

“Showing Us Our Own Face”: Performing Arts and the Human Experience will be on display until May 2020 in Fenwick Library, 2FL.

Follow SCRC on Social Media and look out for future posts in our Travel Series on our Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter accounts. To search the collections held at Special Collections Research Center, go to our website and browse the finding aids by subject or title. You may also e-mail us at speccoll@gmu.edu or call 703-993-2220 if you would like to schedule an appointment, request materials, or if you have questions. Appointments are not necessary to request and view collections.