Newspaper clipping from New York World Telegram, March 25, 1950 detailing the potential effects of the Atomic Bomb, Francis McNamara papers, C0024, Box 57, Folder 7.

This post is part of a series pertaining to SCRC’s current exhibition, Looking Over Our Shoulder: The Cold War in American Culture.

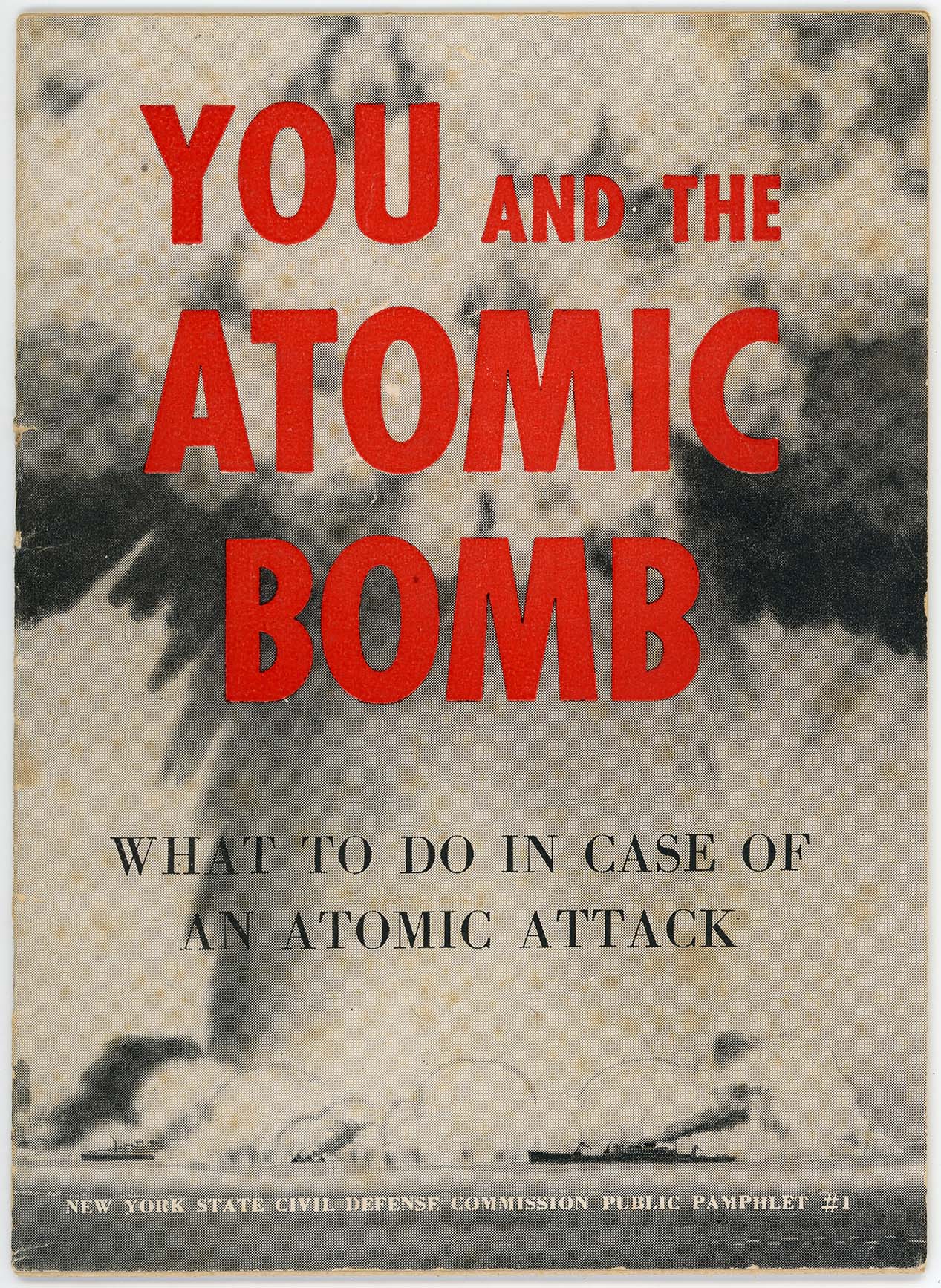

“You and the Atomic Bomb: What to Do in Case of an Atomic Attack” from the Francis McNamara papers, C0024, Box 12, Folder 11.

On August 29, 1949 the Soviet Union successfully tested its first atomic bomb. The weapon was similar in design and explosive power to the United States’ “Fat Man” plutonium bomb detonated over Nagasaki, Japan four years earlier. The Soviets did not make any public statement about this development, but American intelligence agencies discovered evidence that was consistent with an explosion. It was formally announced on September 23 by President Harry S. Truman and confirmed the next day by the Soviet government. In only four years the U.S. monopoly on atomic weapons was over, and the country began an arms race with an enemy that appeared determined to destroy us and our way of life.

Almost as disturbing, it was discovered that the U.S.S.R. received help from U.S. citizens in developing their atomic bomb. In January 1950 Klaus Fuchs, a refugee from Germany and scientist working on the United States atomic weapons program, was arrested and charged with passing classified materials to the Soviet Union. Six months later, it was determined that Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, along with Ethel’s brother David Greenglass, were part of the spy network. During the highly publicized twenty-three-day trial, the Rosenbergs insisted they were innocent, though Greenglass himself testified very strongly against them. They were convicted on March 29, 1951 and sentenced to death. While most Americans thought the trial was fair and the penalty just, there were many who believed the Rosenbergs were innocent. There were large rallies in major cities in the United States and around the world in their support during the two years between their convictions and executions in June 1953.

The Rosenberg Case: Fact and Fiction by Dr. S. Andhil Fineberg, 1953, HX 89 .F48, Special Collections Research Center.

Throughout the Cold War the U.S. government promoted the idea, and many citizens clung to the belief that nuclear war was survivable for those who took the proper precautions and had knowledge of how to protect themselves. The 1951 film Duck and Cover was created by the Federal Civil Defense Administration to teach school children how to protect themselves from a nuclear blast. Its main character Bert the Turtle showed children how to hide under their desks and cover their heads to protect themselves from the effects of a bomb. Oliver Atkins, photographer for The Saturday Evening Post visited a high school in Bethesda, Maryland to photograph the school’s preparations for a Soviet Attack to supplement a story in a 1954 issue. Multiple authors instructed readers how to survive a nuclear attack in books, newspapers, magazines, and pamphlets. Some homeowners took these suggestions to heart, building fully functional bomb shelters in or near their homes.

Bethesda-Chevy Chase High School students practice an atomic bomb drill for photographer, Oliver Atkins to illustrate an article entitled: “This School is Ready for the H-Bomb” in The Saturday Evening Post, September 25, 1954. Oliver F. Atkins photograph collection, C0036, Box 54. Folder 118, Special Collections Research Center.

The 1986 Chernobyl nuclear plant disaster resulted in significant health problems for those who lived in the area. Exposure; Everlasting deals with 30 individuals who survived the event. Exposure; Everlasting by Obara, Kazuma, photographer, 2018. Artist Books TR 655 .O22 2018, Special Collections Research Center.

Organizations decrying nuclear weapons and nuclear energy emerged during this period. SANE (National Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy), which began in 1957 and FREEZE (Nuclear Weapons Freeze Campaign), starting in 1987, helped promote public concerns regarding the proliferation of atomic energy and the arms race. These issues were brought to larger public attention after the Three Mile Island (1979) and Chernobyl (1986) nuclear plant accidents.

Follow SCRC on Social Media and look out for future posts on our Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter accounts. To search the collections held at Special Collections Research Center, go to our website and browse the finding aids by subject or title. You may also e-mail us at speccoll@gmu.edu or call 703-993-2220 if you would like to schedule an appointment, request materials, or if you have questions.