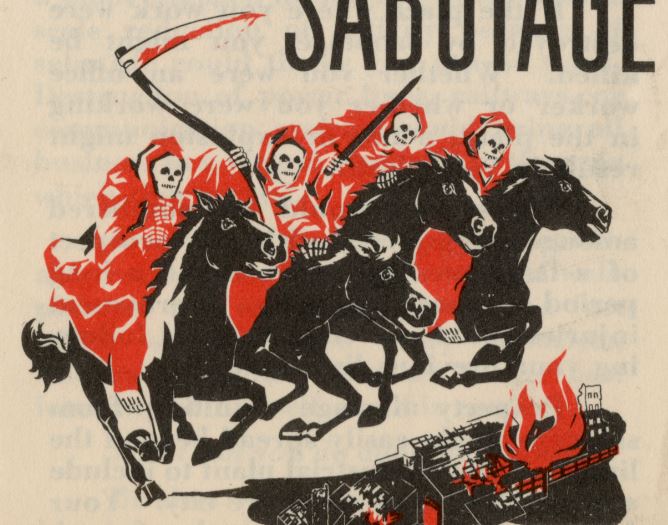

Front/back cover of pamphlet: Disaster Follows Sabotage, Department of Defense, 1953. From the Hayden Peake collection. Special Collections Research Center.

This post is part of a series pertaining to SCRC’s current exhibition, Looking Over Our Shoulder: The Cold War in American Culture. The text was borrowed from the exhibition.

Both the United States and the Soviet Union conducted espionage against each other during the Cold War period. Information in the form of plans, formulas, designs, technologies, or intentions was a key commodity for both sides during this period. It was important for each country to know what their adversary was doing. This information was believed to be the difference between gaining the upper hand or falling behind during a period in which national security stakes were considered high. As computers and satellites were not yet available as tools of spying in the early days, countries relied on humans to penetrate an opponent’s governmental, military, and industrial institutions, steal secrets, and cause mayhem, while remaining undetected as long as possible.

Cover to pamphlet: “Espionage, Sabotage, and Subversive Activities”. Department of Defense, 1953. From the Hayden Peake collection. Special Collections Research Center.

Detail from inside of pamphlet: “Espionage, Sabotage, and Subversive Activities”. Department of Defense, 1953.

From the Hayden Peake collection. Special Collections Research Center.

During the Cold War espionage cases were often the subject of highly-publicized hearings and trials, each seeming more dire than the previous one in terms of danger to United States interests. The 1949 case of Alger Hiss, a junior State Department official who was accused of being a communist spy, was an early and high-profile espionage case. One of his accusers was former communist and Time magazine Editor, Whittaker Chambers. Several years after the case, Chambers wrote a best-selling book, Witness, about the case.

Cold War espionage has also been fictionally depicted in works such as the James Bond series of films, and best-selling novels such as The Spy Who Came In from the Cold (1963) and Tinker, Tailor, Soldier Spy (1974), both by author and former member of British intelligence services MI5 and MI6, John Le Carre.

Follow SCRC on Social Media and look out for future posts on our Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter accounts. To search the collections held at Special Collections Research Center, go to our website and browse the finding aids by subject or title. You may also e-mail us at speccoll@gmu.edu or call 703-993-2220 if you would like to schedule an appointment, request materials, or if you have questions.