The British Isles – made up of the United Kingdom of Great Britain (including England, Scotland, and Wales) and Northern Ireland – are some of the most traveled and beautiful countries in the world. Though not officially considered a part of the British Isles by their own government, Ireland is often associated with this group of nations, and is equally stunning and rich in culture in its own right. For our summer exhibit “Around the World in (Almost) 80 Days,” we here at Special Collections Research Center wanted to ensure that one exhibit case was dedicated to those lovely islands across the pond, with as much representation from its various countries as possible.

Our exhibit case dedicated to materials about or from the British Isles.

Perhaps the most fascinating object in our British Isles case is the rubbing of a 13th century brass engraving. Seemingly made with butcher paper and a waxy crayon, this rubbing from the Bernard Brenner brass rubbings collection depicts a knight dressed completely in armor, a sword at his hip, with his loyal companion – a dog – sitting at his feet.

Close-up of Brass Rubbing of a Knight in the British Isles exhibit case.

Rubbings of brass, stone, or other materials have been practiced for centuries, beginning in China in the 7th century when this method was used to make copies of inscribed stone records.* Perhaps the most well-known usage of rubbings today is gravestone rubbing (though somewhat controversial.) No matter the object, time period, or individual, the idea is essentially the same – to transfer information that the object provides into a more portable format, whether to collect, use later for study, or simply to admire. When it comes to British brass rubbings specifically, our finding aid on the Brenner collection offers some crucial information on this practice:

“Brass rubbing is a technique to reproduce exactly the engraving on a monumental brass. Rubbings are made by carefully pressing paper onto a carved or incised surface so that the paper conforms to features to be copied. The paper is then blacked and the projecting areas of the surface become dark, while indented areas remain white. In Europe the technique of rubbing is almost exclusively applied to monumental brasses. Monumental brasses are usually figures, inscriptions, shields or other devices, engraved in plate brass and laid as memorials. Brasses originated in Europe where they first appeared in the thirteenth century. Brasses in churches are an important source of heraldic information. It was formerly a custom to put a brass over the grave slab, and on this would be shown a figure of the deceased with his armorial bearings.”

Detail of Brass Rubbing of a Knight.

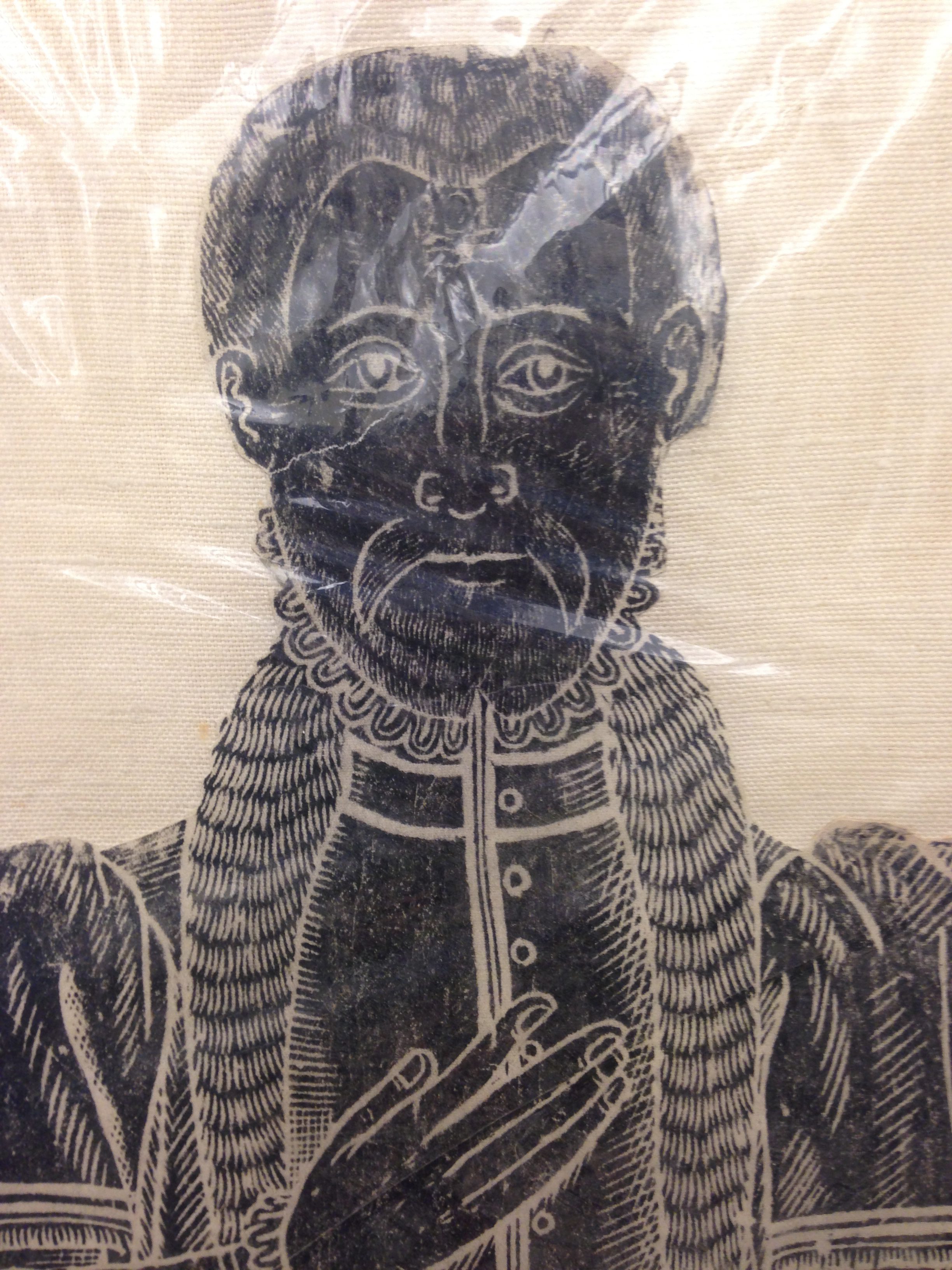

Besides the image of a knight, the Brenner collection also contains some other fascinating figures. One such image is that of a clergyman, cut from its original paper and set against cloth. Gowned in flowing liturgical robes, this priest is clearly of a high rank. With his scepter, beautifully woven chasuble and stole**, prominent hat, and his fingers in the sign of benediction, he cuts an imposing figure.

Brass Rubbing of a Catholic Priest.

Brass Rubbing of a 13th Century British Man.

Another notable rubbing within this collection is petite in stature, but by no means in interest. This rubbing depicts a gentleman in regal attire, with a significant amount of fur draped around his shoulders. The man also boasts a high, lavish collar, a full beard, and holds a book in his hand, likely bound in wood and leather, with leather thong clasps and metal bosses on the cover.***

Detail of Book.

These rubbings as a whole provide snapshots of what life was like in the late Middle Ages, and as evidenced provide invaluable insight into British life during the 13th century.

* http://www.lib.berkeley.edu/EAL/stone/rubbings.html

**The outermost liturgical vestment for a Catholic priest, usually decorated/embroidered. A liturgical vestment made of cloth, worn around the neck.

***Thanks to our Research Services Coordinator Rebecca Bramlett for helping identify the book’s composition.

Our summer exhibition “Around the World in (Almost) 80 Days” runs through August 2017.

Follow SCRC on Social Media and look out for future posts in our Travel Series on our Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter accounts. To search the collections held at Special Collections Research Center, go to our website and browse the finding aids by subject or title. You may also e-mail us at speccoll@gmu.edu or call 703-993-2220 if you would like to schedule an appointment, request materials, or if you have questions. Appointments are not necessary to request and view collections.