This post was written by Ben Brands, L. Claire Kincannon Graduate Intern. Ben has a Bachelors of History from the College of William and Mary, a Masters of History from George Mason University, and is currently a PhD candidate in History at George Mason University.

As the inaugural L. Claire Kincannon Graduate Intern at the George Mason University Special Collections Research Center, I have spent the last few months exploring the Jerome Epstein Collection, and specifically working to transcribe and digitize the letters he wrote while serving in the United States Army during World War II. Epstein was 16 when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor and the United States entered World War II, and enlisted in the Army shortly before his 18th birthday. Following training in Georgia and Louisiana, Epstein served as a radio operator in Italy, which is where he was located on May 8th, 1945 when Germany surrendered unconditionally to the Allies, a day subsequently recognized and celebrated as “Victory in Europe Day”, or more commonly, “V-E Day.”¹

Newsclipping: Daytonians Observe VE-Day

Citation: Scrapbook of World War II Items, circa 1940, Jerome Epstein Papers, C0262, Box 16, Folder 1, Special Collection Research Center, George Mason University Libraries.

Today, on the 73rd anniversary of V-E Day, I would like to highlight some items from the Epstein collection that, I think, speak to the importance and impact of the day. Epstein wrote home regularly while serving during World War II, and his preserved letters provide a unique and valuable view of the war. These letters are reinforced by a scrapbook Epstein’s mother, Rosella Epstein, collected and preserved while Jerome was overseas. In the image to the left you can see the clippings Rosella preserved of the celebration of V-E Day in the Epstein’s hometown of Dayton, Ohio. V-E Day was marked across the United States with massive celebrations, both riotous like those in the first two photos and somber such as that at Patterson Field in the final photo.

Yet in a letter written home from Italy five days later, Jerome Epstein noted that in his unit, the famed 10th Mountain Division, there “was not wild celebration here like there was in the States.” In a revealing passage Epstein continued, saying, “we all say that we will do our celebrating when we are home and have our discharge papers in our hands.” While obviously excited about the German surrender (later in the letter he expresses his relief at no longer having to fear artillery shelling at night), home, and with it an exit from the strictures of Army life, was to Epstein (and presumably many of his comrades) a more powerful call than victory over Nazi Germany.

The lack of celebration among Epstein and his fellow soldiers also reflects a historical context that is hard to recapture today. While we all know now that Japan was destined to surrender a mere three months later following the first use of nuclear weapons in history, at the time this was obviously unknown to 19 year old private soldiers in Italy, and it was believed that it might be years before Japan was fully defeated (indeed, the spectacle of bloody combat on Okinawa that was entering its 6th week as Germany surrendered could not have been encouraging for a quick end to war in the Pacific). In fact, shortly after the German surrender the U.S. War Department produced and distributed a newsreel, Two Down, One to Go, to soldiers serving in Europe in order to begin mentally preparing them for continued war in the Pacific.

Krauts are out

Caption/Citation: Pamphlet produced by the U.S. Army after V-E Day, using text and cartoons to remind soldiers that while the “Krauts were out” there was still Japan to worry about. Some of the caricatures included here have not aged well. Scrapbook of World War II Items, circa 1940, Jerome Epstein Papers, C0262, Box 16, Folder 1, Special Collection Research Center, George Mason University Libraries.

This feeling is also reflected in Epstein’s letter of May 13th, where immediately following his discussion of the muted response to V-E Day he details his “points” under the Advanced Service Rating Score system. This system assigned points for total time in service, time overseas, awards, and dependent children to each individual soldier to determine who would stay in Europe, who would be discharged, and who would be sent to the Pacific. With his 30 points, Epstein could expect to be sent to the Pacific, either with his current unit or as an individual replacement. “I have an amazing total of 30!” Epstein wrote, “I can see myself in the Army years and years from now…it’s too horrible and gruesome to think about. Maybe in 50 years I’ll get another stripe. But then I’d be tripping all over my beard.” Indeed, even with the dropping of the Atomic bomb and the surrender of Japan it would be April of 1946, eleven months after V-E Day, before Jerome was finally able to return home with his discharge papers in his hands for a proper celebration.

The importance of this historical context illustrates both the value of archival sources as well as one of their paradoxes. While these primary sources are invaluable in providing the evidence needed for historians to understand and interpret the past, the researcher will often find himself knowing more about the background, context, and results of events than the contemporaries whose writings make up the archival files. This can especially be true when dealing with war, with its inherent chaos and uncertainty and, in the case of World War II, its efficient system of censorship. When writing from overseas, World War II soldiers’ mail was censored by officers to ensure that no operation details were leaked that could get back to the enemy.

Letters from soldiers overseas had to be read and censored by an officer before they were mailed home. On this envelope you can see the stamp and signature verifying that it has been censored. Jerome Epstein Papers, C0262, Box 1, Folder 4, Special Collection Research Center, George Mason University Libraries.

Thus, in his letter of April 17th, 1945, Epstein wrote cryptically to his parents that “I imagine you have read in the papers about events going on over here lately. The fireworks have started, and the ‘Krauts’ will pay plenty for their evil.” What he couldn’t write was that three days earlier his division had launched a major offensive against the German lines in Northern Italy; what he couldn’t yet know was that on the very day he was writing this letter his division was breaking through the German lines in a victory that would lead to the surrender of all German forces in Italy less than two weeks later. Placing these obscure archival comments into their proper historical context is perhaps the most rewarding part of archival research and this internship.

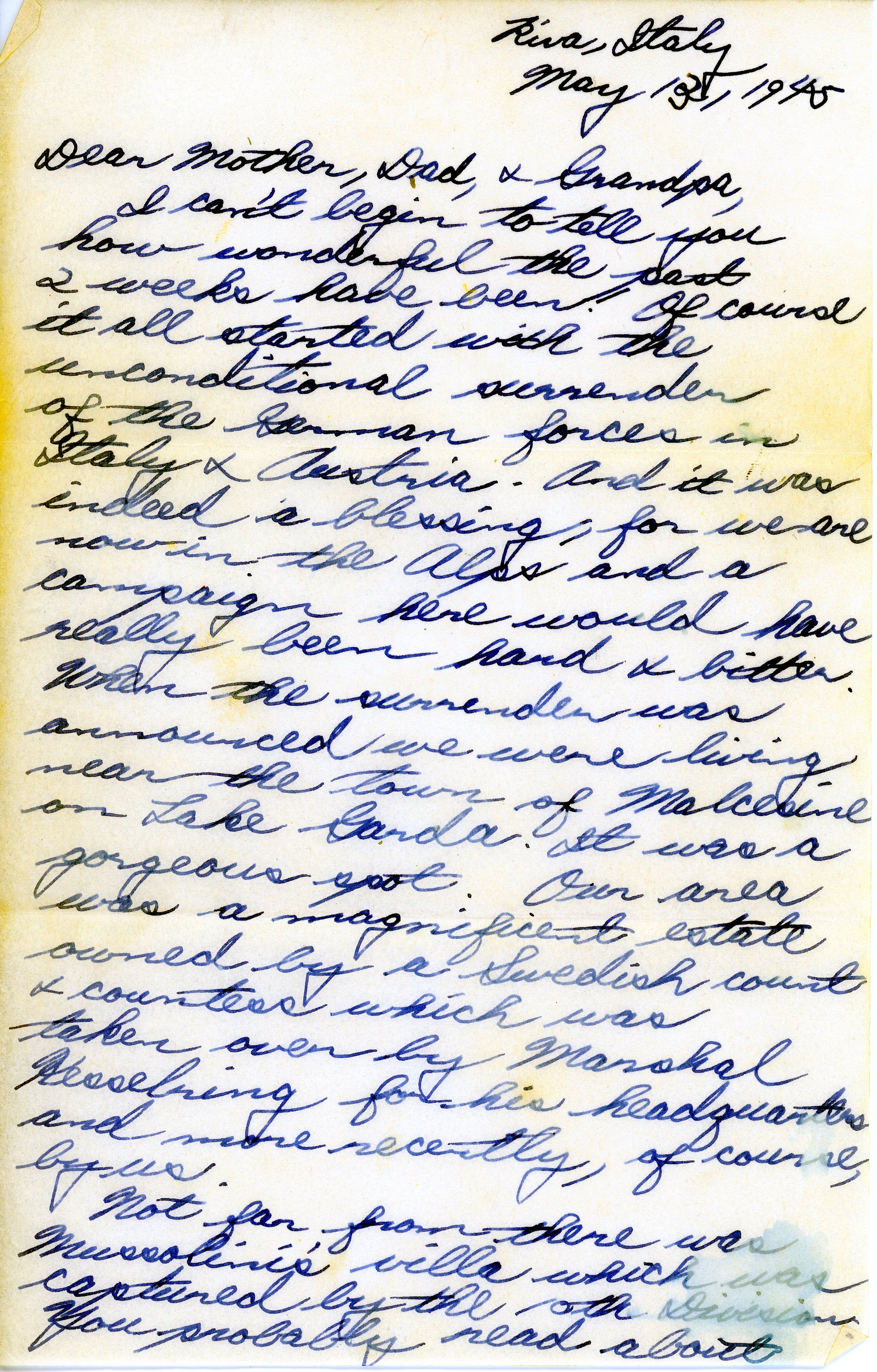

Another great part of this internship has been getting to work in such detail with a single collection. Transcribing every letter written over the course of Epstein’s two plus years of service has allowed me to notice things that aren’t apparent on reading a single letter. For example, on every letter before V-E Day, Epstein starts his header on each page with “Somewhere in Italy.” In his letter following the German surrender he, for the first time, is able to tell his family where he is, writing from “Riva, Italy.” A small change, but one you can imagine had a big impact on a mother who had spent the last four months not knowing where her son was or what he was doing…a perhaps especially poignant detail for a letter sent on Mother’s Day, 1945.

Side by side of Pre/post VE Day letter headings

Citation: Jerome Epstein Papers, C0262, Box 1, Folder 4, Special Collection Research Center, George Mason University Libraries.

I will let Jerome Epstein close this blog entry, since he put it much more eloquently than I could ever hope to: “Then came the surrender, and with it that grand feeling of relief and thankfulness. And our thoughts turned to those who did so much to make this victory possible—those who will never come back.”

¹The actual surrender was signed in France on May 7th, but was then resigned with Soviet participation in Berlin on May 8th. Since by then it was May 9th in Moscow, the Soviet Union recognizes May 9th as “Victory Day” rather than May 8th. Source.

Follow Special Collections Research Center on Social Media at our Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter accounts. To search the collections held at Special Collections Research Center, go to our website and browse the finding aids by subject or title. You may also e-mail us at speccoll@gmu.edu or call 703-993-2220 if you would like to schedule an appointment, request materials, or if you have questions. Appointments are not necessary to request and view collections.

V-E Day – The Jerome Epstein Collection