The post was written by Ben Brands, the 2018 L. Claire Kincannon Intern at the George Mason University Libraries Special Collections Research Center. He holds a B.A. in History from the College of William and Mary and an M.A. in History at George Mason University, and is currently a PhD candidate at George Mason University. He has previously served as an infantry officer in the United States Army and as an Assistant Professor at the United States Military Academy at West Point.

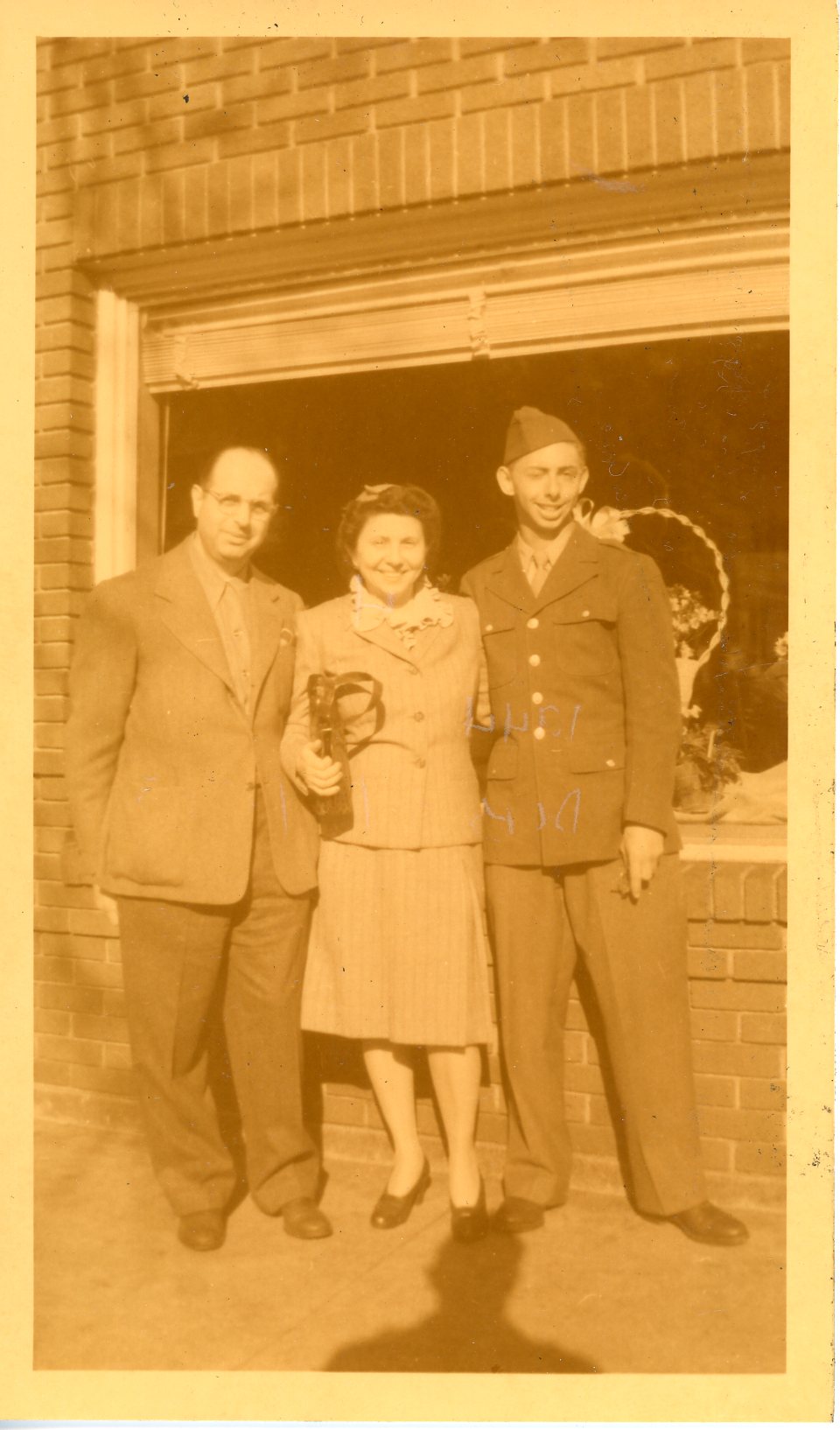

The Epstein family, with Jerome on the right.

As the inaugural L. Claire Kincannon Graduate Intern at the George Mason University Libraries Special Collections Research Center, I had the opportunity to spend the Spring 2018 semester exploring the Jerome Epstein papers, and specifically working to transcribe and digitize the letters he wrote while serving in the United States Army during World War II. Epstein was sixteen when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, and enlisted in the Army shortly before his eighteenth birthday. Following training in Georgia and Louisiana, Epstein served as a radio operator in Italy, where he participated in the final defeat of the German army in the Italian theater as well as the first several months of the post war occupation. Epstein returned to the states a month before the end of the war and served several more months in the Army in Colorado and Tennessee while waiting to accrue enough “points” to earn his discharge.[1]

While Epstein was only a small cog in the massive American war machine that won World War II, and only saw about five months of active combat service, I found working with his letters to be both historically valuable and personally rewarding. Epstein, an 18 year old living away from his family for the first time, was a prodigious letter writer. It is clear from the collection that Jerome was extremely close and open with his family, writing his unvarnished opinions on matters personal, political, military, and social. Indeed, although the Army provided free postage for servicemembers, Epstein paid 18 cents a letter to have his mail delivered by both air mail and special delivery so that he could ensure the fastest possible communication with his family. Considering that Epstein wrote multiple letters a week, often daily, this was a not insignificant investment for a soldier making less than $25 dollars a month for much of the war.

Envelope used and addressed by Jerome Epstein.

Although much of his letters concerned details of the mundane daily life of a soldier in training, he also discussed – at times with surprising insight – some of the most historically significant themes of the war. Epstein’s letters dealt at various points with the dichotomy of serving in an authoritarian organization devoted to fighting for democracy and against fascism (“We are constantly preaching democracy and yet there is nothing in the country that approximates totalitarianism as closely as the Army. I despise saluting, saying ‘yes sir’, being ordered around, etc.”) and the experience of battle (“I don’t think it possible for most writers to express in words the living hell the boys in the infantry go through. It’s without a doubt the roughest toughest branch of service. The other branches go through plenty – make no mistake about that – but it is the infantryman who pushes the enemy back, who slogs ahead inch by inch and foot by foot”), as well as describing some of the lighter scenes of a global war (“we passed through a number of [Italian] cities, including Verona, which Shakespeare wrote so much about and which is the locale for ‘Romeo and Juliet’ and ‘Two Gentlemen from Verona.’ I was determined to recite the balcony scene as we rode through Verona, and did so at the top of my lungs while riding through the streets on top of a 2 ½ ton truck loaded down with equipment and humanity. I don’t think I would have won the Academy Award, however”).[2]

As a soldier of Jewish faith, some of Epstein’s most poignant comments dealt with the complicated relationship between World War II America and prejudice. While the Army hosted a Passover service in Florence, Italy for over 4,000 Jewish servicemembers, an event Epstein described as “the most impressive gathering I have ever attended,” Epstein also dealt with anti-Semitism in the Army as one of his non-commissioned officers discriminated against Jews (as well as African Americans). Indeed, one of Epstein’s fellow soldiers was a Jewish refugee from Germany, and as Epstein wrote to his parents, “he came here to get away from all that [Anti-Semitism and racism], and now finds so very much of it here. He says he always heard of our fine principles and can’t understand why there should be so much prejudice.”[3]

Passover Seder Services Program.

Most of all, Epstein’s letters tell the story of an average American called upon during an exceptional time; a reluctant soldier expected to contribute to the defeat of the greatest threat America and democracy ever faced. And Epstein’s reactions and experiences are perhaps a bit more honest than the traditional story of ideological fervor and patriotic sacrifice. Epstein was not excited about the separation from his family, his subordination to Army discipline and strictures, or the possibility of death in combat. In Epstein’s own words, “All this talk of lofty ideals and postwar aims mean nothing to the average soldier. What he wants is a discharge from the Army and a chance to live like a human being again.”[4] But he went, and served to the best of his ability, and then came home to continue his interrupted life. Indeed, at the close of the war he concluded “I wish every delegate at San Francisco could have been in the front lines before the conference. We all hate to face unpleasant realities, but I never want to forget this war. No American should forget it, and each citizen should do all in his power to prevent a repetition of this human tragedy.”[5] Perhaps there was some overlap in his desire to return home and the talk of lofty ideals.

To be continued in Part Two.

Citations

[1] The Advanced Service Rating System, colloquially known as the “Points System” was how the U.S. military determined who would be sent home and discharged first. Soldiers earned points for time in service, time overseas, and for wounds and valor awards.

[2] Letter from Jerome Epstein, Jr. to Mr. and Mrs. Jerome Epstein and Mr. Lois Green, dated August 19, 1944, Box 1, Folder 3, Jerome Epstein Papers, C0262, Special Collections Research Center, George Mason University Libraries; Letter from Jerome Epstein, Jr. to Mr. and Mrs. Jerome Epstein and Mr. Lois Green, dated March 3, 1944, Box 1, Folder 4, Jerome Epstein Papers, C0262, Special Collections Research Center, George Mason University Libraries; Letter from Jerome Epstein, Jr. to Mr. and Mrs. Jerome Epstein and Mr. Lois Green, dated May 24, 1944, Box 1, Folder 4, Jerome Epstein Papers, C0262, Special Collections Research Center, George Mason University Libraries.

[3]Letter from Jerome Epstein, Jr. to Mr. and Mrs. Jerome Epstein and Mr. Lois Green, dated April 2, 1945, Box 1, Folder 4, Jerome Epstein Papers, C0262, Special Collections Research Center, George Mason University Libraries; Letter from Jerome Epstein, Jr. to Mr. and Mrs. Jerome Epstein and Mr. Lois Green, dated August 19, 1944, Box 1, Folder 3, Jerome Epstein Papers, C0262, Special Collections Research Center, George Mason University Libraries. Hereinafter cited as “Epstein Papers, GMUSCRC” with appropriate item name, box, and folder. See also the program from the Passover Service located in Scrapbook of World War II Era Items, circa 1940s, Box 16, Epstein Papers, GMUSCRC.

[4] Letter from Jerome Epstein, Jr. to Mr. and Mrs. Jerome Epstein and Mr. Lois Green, dated July 2, 1944, Box 1, Folder 2, Epstein Papers, GMUSCRC

[5] Letter from Jerome Epstein, Jr. to Mr. and Mrs. Jerome Epstein and Mr. Lois Green, dated June 20, 1945, Box 1, Folder 4, Epstein Papers, GMUSCRC. San Francisco Conference was the convention that produced the United Nations Charter with the hope of providing international order and preventing future war. Epstein also had some thoughtful comments on the end of the war in Europe. See this post.

Follow Special Collections Research Center on Social Media atour Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter accounts. To search the collections held at Special Collections Research Center, go to our website and browse the finding aids by subject or title. You may also e-mail us at speccoll@gmu.edu or call 703-993-2220 if you would like to schedule an appointment, request materials, or if you have questions. Appointments are not necessary to request and view collections.

The Jerome Epstein Papers – Part One