This post was written by Tavia Wager, Research Services Assistant.

Eleanor of Aquitaine has been examined by many historians, chroniclers, and story tellers over the centuries, but in many ways she remains far more legendary than historical. George Mason University’s (GMU) Special Collections Research Center (SCRC) houses many works which look at Eleanor through various lenses, three of which will be discussed below. She may not be a subject of these works herself, but their analyses of her life in the context of those around her are enlightening not only to the life of Eleanor herself, but to the views and methods of those writing about her. The History of France, published in 1791, The Boy’s Book of Famous Rulers, published in 1886, and The Lion in Winter, published in 1981, from SCRC’s rare book collection, contain varying interpretations of her history, and exemplify contending visions of history from the eighteenth to twentieth centuries.

Title Page to Hereford, Charles John Ann and John Adams. The History of France, from the Establishment of the Monarchy to the Present Revolution. In two volumes. DC 37 .H54 1791 v.1. Special Collections Research Center, George Mason University Libraries.

For many centuries, Eleanor was depicted as more of a villain than a heroine, but she is currently enjoying more extensive treatment by historians, particularly by those with an eye to gender history. Her status as the wealthiest European woman of her time, engagement in the Second Crusade, role as Queen of France and later Queen of England, and the legacy of her own children have cemented her place in history, and tell us far more than we know of most medieval women. Modern historians acknowledge that much of Eleanor’s history is obscured by the misogyny and biases of male chroniclers and historians of subsequent generations; nevertheless, these sources tell us something of her value, as she was deemed important enough to mention at all. In my opinion, her mistreatment by chroniclers and historians over the centuries says more about the problematic nature of uncovering the history of women in the Medieval period than about Eleanor herself. The three books I have chosen demonstrate that Eleanor’s historical narrative has evolved over time, but nonetheless continue to present a historical vision which cannot be reconciled by evidence.

To explore the eighteenth century depiction of Eleanor, I chose to analyze Hereford and Adams’ The History of France, published in 1791. Though their subject is vast, they still take the time to remark upon Eleanor, reflecting the important place she held in eighteenth century historiography. They accept unequivocally the predominant perception of Eleanor as she was portrayed by earlier chroniclers and historians. Though modern scholars give far more credence to Eleanor’s agency in accompanying her husband, Louis VII, on Crusade and leading her own retinue, Hereford and Adams do not address Eleanor’s presence on Crusade until remarking upon her alleged affair with her uncle. “He [Louis] was received with open arms by Raymond of Poitiers…but to public calamity succeeded domestic misery; and it could not be concealed from the eye of a tender husband, that the fidelity of his queen Eleanor had been sacrificed to repay the hospitality of Raymond.”[1] They assign Louis the role of loving husband and pious crusader, carting his wife along as baggage. This interpretation has fallen largely out of fashion today, with historians concluding that Eleanor chose to go on Crusade herself for various personal and strategic reasons. Regarding Louis’ actions during the Crusade, Hereford and Adams fail to remark upon the political and strategic tensions that led to his departure from the East, largely blaming his exit to the behavior of his queen, particularly in her affair with Raymond. “From this scene of dishonor, Lewis, accompanied by his reluctant queen, hoisted sail for Jerusalem, and rejoined in the sacred city the former rival of his glory, the present partner of his distress.”[2] Upon their return to France, they remark only on Louis’ motivations for divorce from Eleanor regarding her apparent infidelity, where modern historians rather comment on Eleanor’s own motivations for divorcing her husband. “But his thoughts [Louis’] were soon after entirely engrossed by a care of a more domestic nature: the levity of his wife Eleanor, and her suspicious partiality for her uncle Raymond, prince of Antioch, were deeply engraved on his mind…and he determined to divorce from his bed, a licentious female.”[3] Though their remark provides no evidence, the fact that she is discussed at all is remarkable, and reminds us of her importance.

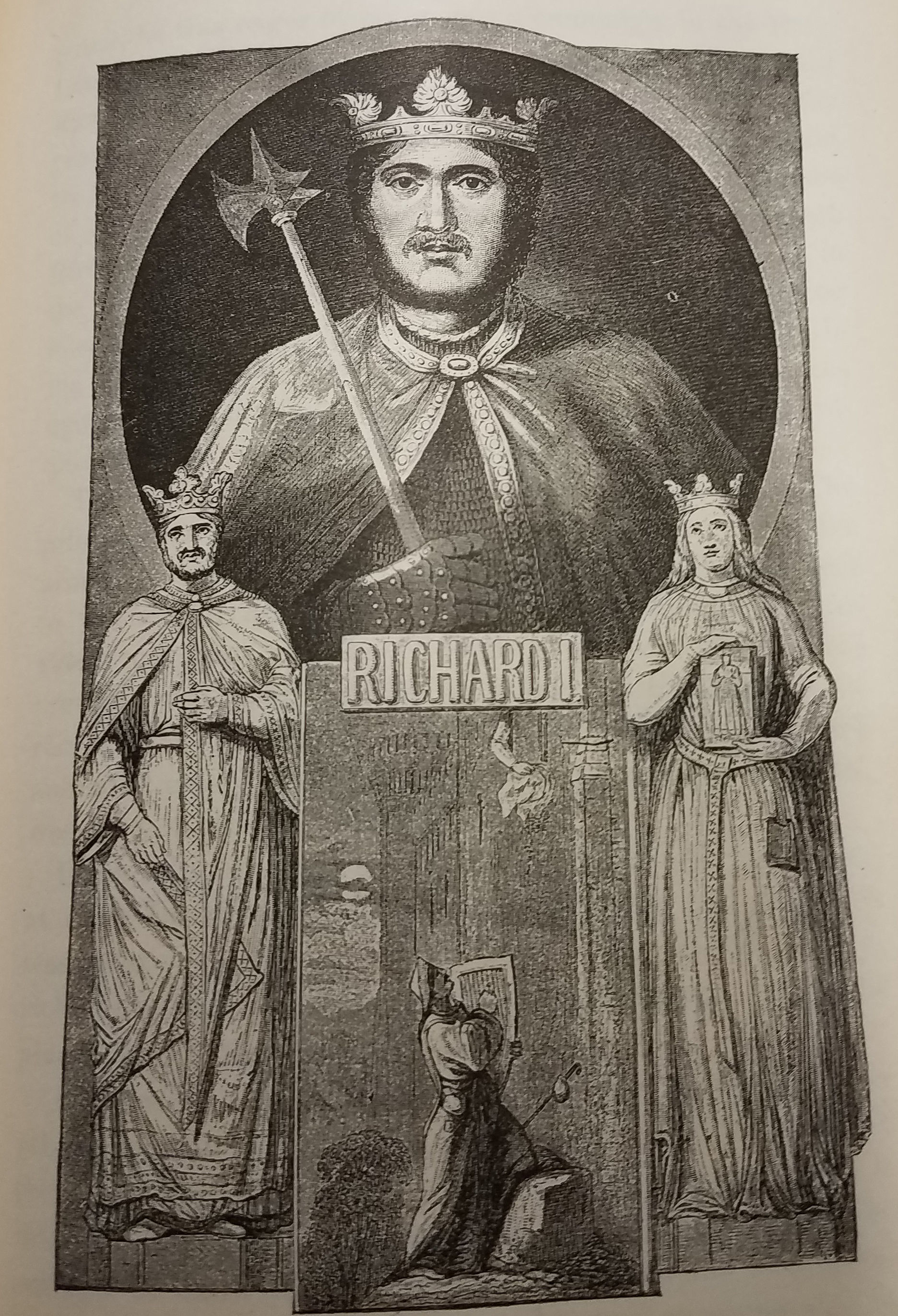

The Boy’s Book of Famous Rulers, published in 1886 by Lydia Hoyt Farmer, includes a section on “Richard Cœur de Lion,” and it is quite telling of Eleanor’s value that Farmer dedicates several pages to her, specifically regarding her early life. She gave Eleanor more agency

Richard the Lion Heart between his parents, Henry II on the left and Eleanor of Aquitaine on the right, from Hoyt, Lydia, The Boy’s Book of Famous Rulers, D107 .F3 1886, Special Collections Research Center, George Mason University Libraries.

than Hereford and Adams, remarking that “King Louis VII., her husband…determined to go on crusade, and queen Eleanor, from a gay love of adventure, resolved to accompany him.”[4] Over the course of a century, Eleanor shifted from an object brought along by her husband, to an active and decisive participant in the Second Crusade. At first this appears to be a more modern interpretation of Eleanor, but Farmer quickly describes her and the ladies who accompanied her as a burden, “the crusading expedition, which should have been composed of an army of valiant warriors, became an immense train of women and baggage.”[5] Eleanor’s time on Crusade is colored by her alleged affair with her uncle and eventual divorce, and she remains a villain of the Crusade though many modern historians have remarked there was little contemporary evidence of such behavior. Farmer does not refer to the affair with her uncle outright, perhaps due to her audience; she writes that “Queen Eleanor so displeased King Louis by gay and frivolous conduct, that a long and serious quarrel arose between them, and he declared he would obtain a divorce from her.”[6] It appears that Farmer blames Eleanor for her divorce, but acknowledged that dissent remained among historians regarding these events. “Some historians place the blame of the divorce upon Eleanor, some upon Louis; but all unite in condemning her previous conduct, for she occasioned many scandalous remarks by her undignified, unwifely, and even culpable actions.”[7] Even when she accepted the lack of evidence, she argued that it was historically certain that Eleanor engaged in behavior unbecoming of a queen. Farmer’s evaluation of Eleanor’s behavior may be more moderate than that depicted in The History of France, but modern historians have come to conclude that, due to lack of contemporary evidence, the affair between Eleanor and her uncle is highly unlikely. Despite this, the perpetuation of her alleged affair became cemented into the minds of many twentieth century scholars.

Though much is made of Eleanor’s time during the Second Crusade, she is also remembered for her time as Queen of England, described by many as a villainess, envious of her husband Henry II’s mistress and plotting with their sons to overthrow him. James Goldman explores this period in The Lion in Winter, originally produced in 1966, and since made into several films, representing the popular view of Eleanor as she was conceived in historical imagination. In the 1981 publication of the play, Goldman explored the relationship between historians

Rosemary Harris and Robert Preston as Eleanor of Aquitaine and Henry II, in 1966, insert from Goldman, James. The Lion in Winter, PS 3513.O337 L5 1981. Special Collections Research Center, George Mason University Libraries.

and storytellers: “Historians and storytellers don’t have much in common, but they do share this: the past once it gets hold of you, does actually come alive. For scholars this is troublesome. For writers, it’s the good stuff.”[8] Though he is not seeking to be a historian, nor to tell a historically accurate narrative, The Lion in Winter represents the vision of Eleanor as she was seen in the twentieth century historical imagination. Goldman acknowledged there were no sources to account for the true character of the people he has chosen to portray. Thus, where Hereford and Adams do not discuss their source materials, and Farmer acknowledges it briefly, Goldman finds, in the lack of sources, a greater license for his own creativity and imagination rooted in earlier histories. Though his play takes place in 1183, long after the Second Crusade, he refers to her earlier life, and perpetuates the myth of Eleanor as an Amazon warrior, though he does not explicitly recount the tale of her affair with Raymond. As Eleanor says in the play, “I even made poor Louis take me on Crusade. How’s that for blasphemy? I dressed my maids as Amazons and rode bare-breasted halfway to Damascus. Louis had a seizure and I damn near died of windburn but the troops were dazzled.”[9] The contradictions between a twentieth century perspective and the earlier works discussed here are clear: Goldman’s Eleanor forced Louis to take her on Crusade, where Hereford and Adams fail to address her reasoning or lack thereof for accompanying her husband, and Farmer assumes she wanted to attend out of a love of adventure.

In analyzing these three sources, held in the George Mason University Special Collections Research Center, it is clear that Eleanor of Aquitaine remains a controversial historical figure among historians and in popular historical imagination. Eleanor has transitioned from an object, to an agent capable of making her own decisions, to a woman forcing her husband to acquiesce to her desires, to a nuanced historical character who may or may not be representative of women of her time. Due to a lack of historical evidence, and a thousand years separation, we will likely never be able to uncover the historical woman from her legend. Nonetheless, these legendary qualities have kept her alive in the minds and imaginations of historians and writers, and thus we know far more about her than about many medieval woman, who have been silenced by the centuries and the early construction of history by men. Examining past historical works enlightens us as to the roots of our own perceptions of history, and demonstrates the changing nature of historical figures.

Follow Special Collections Research Center on Social Media at our Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter accounts. To search the collections held at Special Collections Research Center, go to our website and browse the finding aids by subject or title. You may also e-mail us at speccoll@gmu.edu or call 703-993-2220 if you would like to schedule an appointment, request materials, or if you have questions. Appointments are not necessary to request and view collections.

[1] Charles John Ann Hereford and John Adams, The History of France, from the Establishment of the Monarchy to the Present Revolution. In two volumes. (Dublin: Printed for J. Moore, 1791), 158. DC 37 .H54 1791 v.1. Special Collections Research Center, George Mason University Libraries.

[2] Ibid, 158.

[3] Ibid, 161.

[4] Lydia Hoyt Farmer, The Boy’s Book of Famous Rulers (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell & Co., 1886), 201. D107. F3 1886. Special Collections Research Center, George Mason University Libraries.

[5] Ibid, 202.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid, 203.

[8] James Goldman, The Lion in Winter, (New York: Random House, 1981), iv. PS 3513.O337 L5 1981. Special Collections Research Center, George Mason University Libraries.

[9] Ibid, 40.