This post was written by Tavia Wager, Research Services Assistant.

The George Mason University Special Collections Research Center is lucky enough to have two collections of brass rubbings, one donated by Vida Beaven, and the other by Bernard Brenner. This collection gives researchers the invaluable opportunity to study material culture, images of identity, and practices of commemoration in the medieval period.

What is a Monumental Brass?

Monumental brasses became popular during the medieval period in Europe funerary effigies. A monumental brass is defined as a “sepulchral tablet of brass (or latten), bearing a figure or inscription, laid down on the floor or set up against the wall of a Church.”[1] The practice of creating monumental brasses evolved from the tradition of making incised slabs, which in turn were made from the ninth century onwards. Resins and metals were inlaid into the slabs to give a more detailed and long lasting portrayal of the subject.[2] They were produced throughout Europe, but due to the large-scale destruction on the Continent during the Reformation and later conflicts, far more brasses are found today in England, totaling approximately three thousand.[3] As a result, making brass rubbings has become a pastime for many historians, hobbyists, and conservators, as well as societies like the Monumental Brass Society. The Monumental Brass Society, of which Bernard Brenner was a member, published numerous works on monumental brass and its techniques.

The Evolution and Practice of Brassing

The Cambridge University Association of Brass Collectors was formed by Cambridge undergraduates in 1887, who sought to preserve and record monumental brasses. Although they began by focusing on medieval and early modern brasses, the group eventually extended into an examination of brasses into the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.[4] Known today as the Monumental Brass Society, they argue that the brasses in England are exceptional, worthy of preservation, and ought to be recognized as a national treasure.[5] According to Cecil T. Davis, in The Monumental Brasses of Gloucestershire, monumental brasses “clearly mark the successive steps of our nation’s progress….[giving] insight into the currents of thought and feeling which deeply moved our forefathers.”[6] Brass rubbings are a visual window into the past, conveying the culture and practice of mourning and commemoration in the medieval period.

Although the practice of making brass rubbings began as a hobby among enthusiasts, it quickly became a tool for historians and conservationists. The Society represents an endeavor to do far more than organize hobbyists, as they indicate that conservation and preservation are some of the most important objectives of the Society. In this, we are reminded of the recent destruction of Notre Dame; we must continue to preserve monumental brasses where they are found, as well as through reproductions in brass-rubbing, as it is impossible to entirely assure their safety for future generations.

Brass Rubbings

The Brenner Collection presents the researcher with rubbings of various subjects, including women, children, men, soldiers, priests, and animals. Material culture plays a huge part, as the appearance and vestments of the subjects are presented visually, where they were not often recorded in written sources. The representations of soldiers in armor, for example, tell us much about the way in which armor was constructed and wore. There was a persistent perception that soldiers depicted with crossed legs were Crusaders, however this interpretation has been largely debunked by scholars.[7] Figure four depicts two brothers, both in armor with uncrossed legs, who died in different years but are shown together in effigy.[8] The highly detailed portrayal of their armor is invaluable to researchers, as even this representation of brothers demonstrates the variations in style of armor and weapons. Furthermore, the depiction can even tell us how these individuals and men in society at large wore their facial hair.

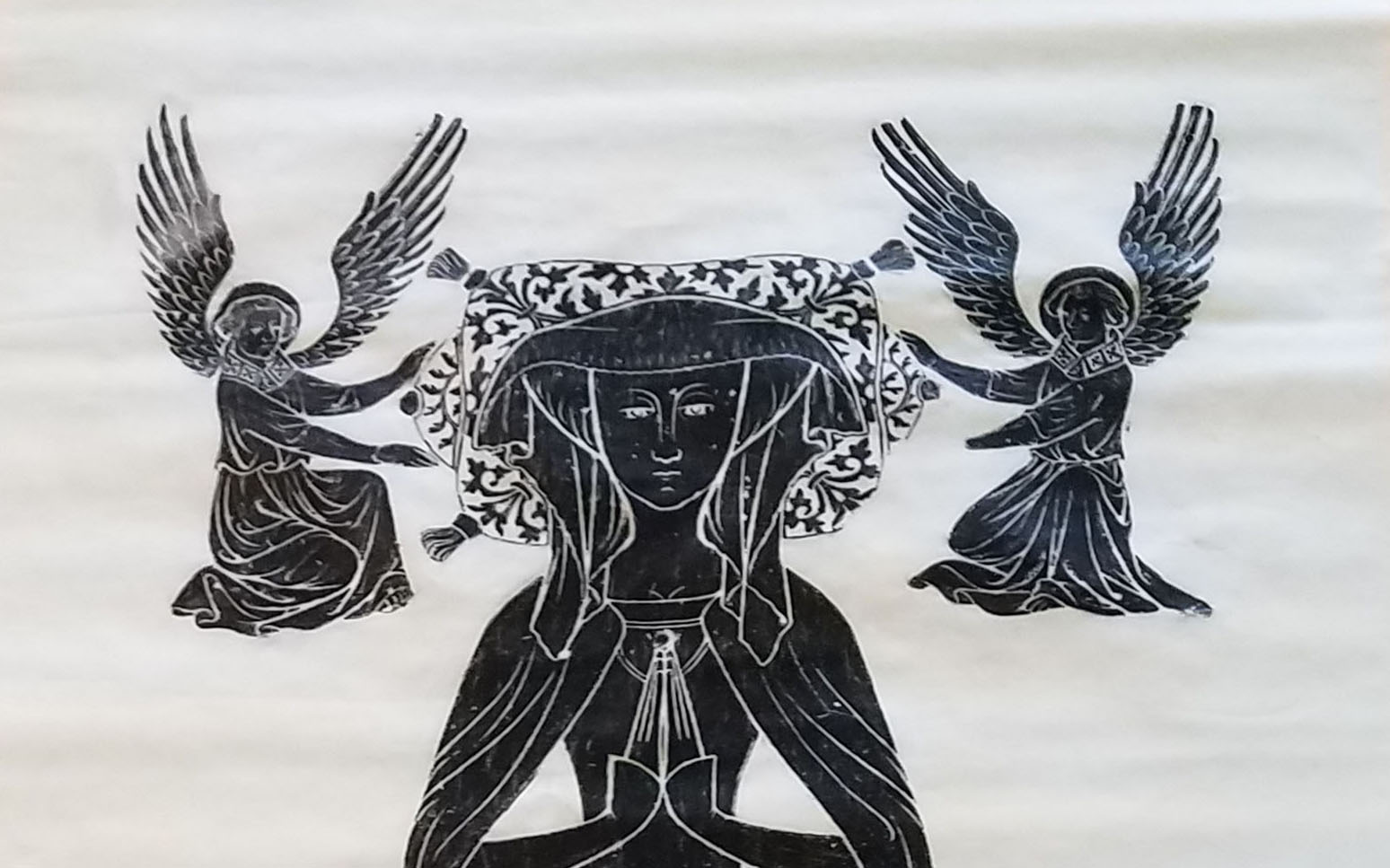

Women are frequently depicted in monumental brasses, as memorials of themselves or as wives. Men are often shown with more than one wife if they married more than once, and some women with two husbands. Figure one, for example, shows a couple memorialized together, Thomas and Margery Burton, in 1419, with Thomas in his suit of armor and Margery in an elaborate headpiece to signify their wealth and status.[9] Figure five shows a solitary woman, Isabel Plantagenet, daughter of Richard, Earl of Cambridge, and wife of Henry Bourchier, Earl of Essex and great-granddaughter of Edward III. With her elaborate head dress and garments, she is depicted as a woman of status, which may be why she stands as a solitary individual rather than alongside her husband. Unlike most women, she is shown standing upon a griffin, perhaps signifying her status as a noblewoman. Her position standing upon the griffin is also significant, as most animals are shown sitting upon the robes or dresses of their female owners, while men stand upon animals.[10]

As a public image of identity and status, the presence of pets in medieval funeral effigies suggests that pets were important for individuals in life as well as in death. Scholars suggest that pets also convey the wealth and social status of the subject; by depicting the dog with a jewel-studded collar, the artist suggests the wealth of its owner, and by depicting the dog as full-bellied, suggests it is well fed. Like other aspects of material culture, pets may not have been written about in the sources available to us today, but monumental brasses and brass rubbings remind us of the importance of the connection between humans and animals, in the medieval period as it is today.

The Bernard Brenner Monumental Brass collection at the George Mason University Special Collections Research Center presents a special opportunity for students and researchers alike to examine spectacular examples of art and culture from an era utterly unlike our own. Monumental brasses were made to remind the living of the dead, and were designed to present the best representation of their subject. As such, we can look at them today as representations of personal and public identity, and as a visual example of material and intellectual culture, preserved today by hobbyists, conservationists, and historians.

This post is the second post about the Bernard Brenner Brass Rubbings collection. You may view the first part here.

Follow Special Collections Research Center on Social Media at our Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter accounts. To search the collections held at Special Collections Research Center, go to our website and browse the finding aids by subject or title. You may also e-mail us at speccoll@gmu.edu or call 703-993-2220 if you would like to schedule an appointment, request materials, or if you have questions. Appointments are not necessary to request and view collections.

Works Cited and Figures

1. Brenner, Bernard. “Thomas and Margery Burton.” 1381 All Saints, Little Casterton Rutland. Bernard Brenner Brass Rubbings Collection, C0044, Box D Roll 5. Special Collections Research Center, George Mason University Libraries.

2.Brenner, Bernard. “Margaret Cheyne.” 1419, Hever, Kent. Bernard Brenner Brass Rubbings Collection, C0044, Box D Roll 2. Special Collections Research Center, George Mason University Libraries.

3. Brenner, Bernard. “Robert and Thomas Swynebourne.” 1391 Little Horkesley, Essex. 8/19/1986. Bernard Brenner Brass Rubbings Collection, C0044, Box J, Roll 9. Special Collections Research Center, George Mason University Libraries.

4. Brenner, Bernard. “Isabel Plantagenet.” 1483, Little Easton, Essex. 10/29/1979. Bernard Brenner Brass Rubbings Collection, C0044, Box D Roll 7. Special Collections Research Center, George Mason University Libraries.

[1] N.J. Rogers “English Episcopal Monuments, 1270-350: The Origins of Monumental Brasses,” in The Earliest English Brasses: Patronage, Style, and Workshops, 1270-1350, edited by John Coales, (London: Monumental Brass Society, 1987), 8.

[2] “The Monumental Brass Society,” http://www.mbs-brasses.co.uk/The%20MBS.html. Accessed April 8, 2019.

[3] Sally Badham and Martin Stuchfield, Monumental Brasses (Oxford: Shire Publications Ltd., 2009), 5.

[4] “The Monumental Brass Society,” http://www.mbs-brasses.co.uk/The%20MBS.html. Accessed April 8, 2019.

[5] J.C. Page-Phillips, “Forward by the President of the Monumental Brass Society,” in The Earliest English Brasses: Patronage, Style, and Workshops, 1270-1350, edited by John Coales, (London: Monumental Brass Society, 1987), viii.

[6] Cecil T. Davis, “Preface,” In The Monumental Brasses of Gloucestershire. London: Phillimore & Co., 1899.

[7] Harris, O. D. (2010). “Antiquarian attitudes: crossed legs, crusaders and the evolution of an idea”. Antiquaries Journal. 90: 401–40.

[8] “Robert and Thomas Swynebourne,” 1412. 1391 Little Horkesly, Essex. 8/19/1986. Bernard Brenner Brass Rubbings Collection, C0044, Box J, Roll 9. Special Collections Research Center , George Mason University Libraries.

[9] “Thomas and Margery Burton,” 1381, All Saints, Little Casterton, Rutland. Bernard Brenner Brass Rubbings Collection, C0044, Box D Roll 5. Special Collections Research Center , George Mason University Libraries.

[10] “Isabel Plantagenet,” 1483, Little Easton, Essex. Bernard Brenner Brass Rubbings Collection, C0044, Box D Roll 7. Special Collections Research Center , George Mason University Libraries.