The events of September 11, 2001 have been on my mind a lot lately.

I should explain why that’s unusual for me. You see, I was only 10 when the planes hit the World Trade Center, and though we lived in New York state at the time, the horror unfolding in the city seemed far away. I was shaken, yes, but the way many of us lucky enough to have escaped the worst outcomes of that day were shaken—it was more the shock, the fear, the uncertainty, and the threat of war that resonated. Those are the emotions that I revisit every year when we mark the anniversary of that day.

But in 2021, the year of the 20th anniversary of 9/11, the reality of that day has shown up a lot of different ways in my life. Earlier this year, on a standard recommendation from a friend, I read The Only Plane in the Sky: An Oral History of 9/11 (Simon & Schuster, 2020), a compendium of first-person accounts. A week ago, I sat down with my husband to watch Worth, a new Netflix movie about the administration of the 9/11 Victim Compensation Fund, which, though not a documentary, incorporated the very true stories of actual families still reeling from the losses they experienced that day. Strangely, a few days after that, at a restaurant in Delaware, my husband and I happened to end up chatting with an older couple—one of whom wore a 9/11 memorial pin—only to find out that he wore it because he had been on the 105th floor of the South Tower when the North Tower was hit. A lot of fateful decisions saved his life. Of course, the end of the war in Afghanistan and resurgence of the Taliban have also brought up a lot of complicated remembrances about 9/11 and the riptide of emotions that brought us into that war in the first place.

So this week, when I came across the copy of GMU’s student publication Broadside for September 13, 2001, as part of a new project digitizing these papers, I felt it was yet another cosmic message that I needed to pause and reflect on what happened September 11, 2001 and give some space to reading about how the attacks impacted real people. Using the articles from these old newspapers, I got another glimpse into that day.

Photographs of students reacting to the September 11th attacks. From the GMU Broadside newspaper.

GMU’s geography, I think, made the attack feel all the more threatening and all the more personal. Some students on the Arlington campus recalled feeling the ground shake with the impact of hijacked American Airlines Flight 77 slamming into the Pentagon.[1] For those on Fairfax campus, the news spread quickly, and many were drawn to the News Center that existed in the Johnson Center at that time. Student reporters described the scene: “Rapidly gathering around the television sets on the first floor of Johnson Center, students and faculty alike watched in eerie silence as their morning disintegrated into a mass of fear, anger, numbness and shock.”[2] One College of Arts and Sciences student said “40 years from now I will be able to remember every detail of this day as if it happened yesterday.”[3]

GMU students watching the news unfolding. From the GMU Broadside newspaper.

As with the rest of the nation, George Mason University campus seemed to stand still. Athletics games were cancelled. Vigils were organized. Tears were shed. Yet, once the initial shock turned into full emotional realization, the feelings became complicated. GMU’s student government organized a program—called GMU Unite—the evening of September 11th, which was attended not just by students, but also by the Vice President of the University Life and then-University President Alan Merten. As described by Broadside reporters, no one seemed to know how to feel. “At times,” they wrote, “the emotional debates circled around topics ranging from feelings of helplessness, to anger, to a desire for revenge and retribution.”[4]

That desire for retaliation is evidenced in the next several editions of the Broadside, as numerous opinion pieces advocated for the United States to flex its might against the perpetrators of 9/11, while others preached that “an eye for an eye makes the whole world blind” (a quote apocryphally authored by Gandhi).[5] Many students felt war was the only appropriate response, but some students used to the newspaper to call for a more measured calculation. In this way, George Mason reflected the rest of the country, which was also sorting out how exactly to address the deep emotions brought on by the terrorist attacks. That confusion and uncertainty on how to act permeated the University as well.

What’s most interesting about the Broadside’s coverage of 9/11 and its aftermath was the space it gave to Muslim and Middle Eastern voices following the attacks. The editors seemed to understand immediately that some of that desire for retaliation would rain down on entirely innocent people who were lumped in with terrorists based upon their religion, country of origin, or appearance; they also seemed eager to push back against that impulse. One of the Broadside’s staff writers at the time who was both Muslim and Palestinian took up several inches of print to describe how his own grief at the 9/11 attacks was compounded by fear of rage misdirected toward them. “I am Muslim and a Palestinian,” he wrote. “For some reason, because this is my heritage and descent, I am automatically implicated as having participated in this horrific act…..Many Muslims who were born and raised here feel the same pain, frustration and loss that other Americans feel. Just because we have a different kind of name or dress differently does not make us any less American than anyone else.”[6] Even weeks later, a Palestinian student wrote their experience on 9/11: “I didn’t know what to do or what’s going to happen next. Who’s going to come up to me and say, ‘you’re a Palestinian who killed us.’ Shall I worry about myself, my sister, or my parents back home? Where should I go? I am not safe here and I am not safe [in Palestine]. I want to go home [but] I can’t.”[7]

A photograph of Muslim students at a vigil held to protest racial and religious harassment post-September 11th. From GMU Broadside newspaper.

The fears of these students were founded in unfortunate reality. The calls for unity and pleas from Muslim or Middle Eastern students for understanding did not stop a group of GMU students from chalking “Death to Islam” and body outlines on the sidewalks in front of the Johnson Center.[8] It didn’t stop so many incidents of abuse that there had to be a separate candlelight vigil the week of September 27, this time for the victims of on-campus religious and racial harassment.[9] The healing for some of these issues came in the form of empathy from others, such as GMU alumna Michelle Hankins. She wrote in to the Broadside with this reminder: “Many Arabs have been where we Americans are today. They have had family hilled, their nations have waged wars against one another, they have walked down streets in fear. I have known Arabs in the United States franticly called family back in their home nations, wondering after a bombing or attack in their homeland if their family was okay.”[10] This is the type of understanding many targeted students pleaded for.

Perusing the post-9/11 editions of the Broadside, it’s clear that the University was a microcosm of what was happening in the rest of the nation, both good and bad. On campus, there was shock, mourning, gathering, a drawing together. There was also division, hatred, and fear. There were moments of silence and moments of screaming. There was hopelessness and there was hope.

On this anniversary of September 11th, we can remember all of that. It’s okay if we are still making sense of what happened 20 years ago today. In honesty, we probably won’t ever really understand. But reading these articles reminded me that we are all together in our confusion and anguish, even as we remember this event from two decades ago. And perhaps, all together, we can continue to find hope for a better world.

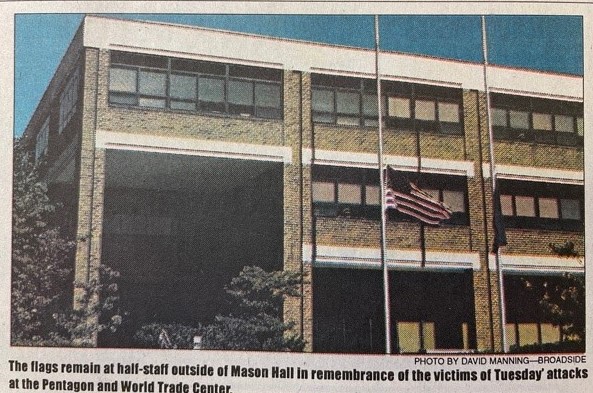

Flags flying at half-staff in memory of the victims of the September 11th attacks. From the GMU Broadside newspaper.

[1] Broadside, September 13, 2001, Vol. 69, No. 5.

[2] Anh Phan and David Sullivan, Broadside, September 13, 2001, Vol. 69, No. 5.

[3] Renu Ahuwalia, Broadside, September 13, 2001, Vol. 69, No. 5.

[4] Anh Phan and David Sullivan, Broadside, September 13, 2001, Vol. 69, No. 5.

[5] Broadside, September 17, 2001, Vol. 69, No. 6.

[6] Mousa Hamad, Broadside, September 13, 2001, Vol. 69, No. 5.

[7] May Sanda Soe, Broadside, September 27, 2001, Vol. 69, No. 9.

[8] Anh Phan, Broadside, September 13, 2001, Vol. 69, No. 5.

[9] May Sanda Soe, Broadside, September 27, 2001, Vol. 69, No. 9.

[10] Broadside, September 17, 2001, Vol. 69, No. 6.

Follow SCRC on Social Media on our Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter accounts. To search the collections held at Special Collections Research Center, go to our website and browse the finding aids by subject or title. You may also e-mail us at speccoll@gmu.edu or call 703-993-2220 if you would like to schedule an appointment, request materials, or if you have questions.