This post was written by Teo Rogers, Digitization Student Assistant for the C-SPAN records Digitization Project.

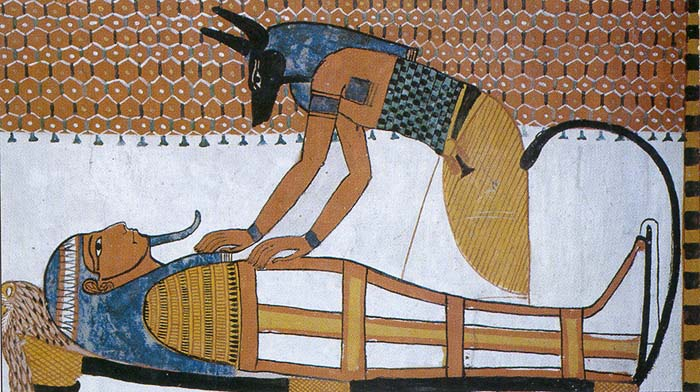

You are a priest in ancient Egypt. Picture yourself in a dark workshop, lit only by a few flickering torches affixed to walls of ancient stone. The Anubis mask you wear is heavy, but you are largely unencumbered by its weight; you have recited the necessary spells and correctly performed the rituals to effectively become the god of embalming, at least temporarily. The four canopic jars stand at the ready to receive the innards of the deceased person on whom you’re about to begin the arduous process of mummification. However, on the slab in front of you is not a body, but a gray box. Confused, you open it, only to find folder after folder separated by categories like “Complaints,” “Book Notes,” and “Rush Limbaugh.” (Somehow, you can read the English language perfectly.) You flip the box back to the front and see the words “C-SPAN Viewer Mail” written in black ink. You’re even more confused now. And what happened to the body you were supposed to be embalming?!

Now, you might be just as puzzled as your ancient Egyptian sacerdotal persona as you read this through the luxury of the Internet. You’re probably thinking, “What does mummification have to do with C-SPAN and the interesting work the SCRC is doing?” This is a fair question, and in truth, it’s not the literal physical elements of mummification that I’m comparing the SCRC work to. Nobody sends us bodies to embalm; we don’t work by torchlight (except we do sometimes work in the dark); and, alas, our physical archive probably won’t last for 4,000 years. We do wear masks, although they’re not Anubis masks, but a byproduct of the ongoing pandemic. Instead, we’re taking a deep dive into the lands of metaphor and analogy!

Allow me to clarify something first, though. It’s a common, but understandable, misconception that the ancient Egyptians were obsessed with the idea of accepting death. No other ancient civilization has left us with so many elaborate structures, so much funerary paraphernalia, so many writings, artworks, and inscriptions that tell us about mortuary ritual behavior and hint at the philosophy of and religious beliefs about death, as Egypt has. At first glance, it’s easy to characterize Egyptian culture as a culture obsessed with the acceptance of death and dying. This is not the case.

In his book Death and Salvation in Ancient Egypt, German Egyptologist, religious scholar, and this author’s current celebrity crush, Jan Assmann (yes, that is his name), posits that the Egyptians engaged in a cultural effort to deny death, to rebel against it, but did not repress it. The preoccupation with death was more about ensuring the continuation of life, in both a social and individual sense, after death. Assmann succinctly explains that “the Egyptians hated death and loved life” (17). The “death” that the Egyptians hated was not just the biological termination of life, but death as a severance of the self from the social and cultural whole. The Egyptians viewed themselves not as “isolated elements” of a social aggregate; social isolation was death. Importantly, this worldview was extended to the Egyptian conception of the body, too. Within this perception of the body as social structure, the heart was understood to be the center of it all.

Thus, when a person died, not only did they…well, die, but they were also (temporarily) “dismembered” from society. If the heart stopped “speaking,” all was lost. This is why they hated death, and why they developed such a profound corpus of counterimages to deny it, as Assmann calls it, which constituted a whole counterworld in which death could be overcome, not through a “construct of fantasy and belief,” (18) but one that required meticulous planning to conquer death. In the Instruction of Hardjedef (written approximately 4,500 years ago, during the last dynasty of the Old Kingdom), this attitude is made known pretty explicitly when we read “the house of death [the tomb] is the house of life,” (17-18). Such a mindset would last the duration of ancient Egyptian civilization.

But how did the “house of death” become “the house of life”? Let’s start with a quick word on mummification, “specifically intended to remedy the condition of dismemberment and decomposition” that came with death (30). The mummification process was typically carried out in an embalmer’s workshop called the wbt, which Ann Rosalie David translates to “place of purification.” (235). The process took a LONG time, but the goal was to prepare the body for burial and to reunify the dead by giving them agency over their body once more. Embalmers removed the body’s internal organs and placed them into canopic jars, except for the heart, which was placed back into the body at a later time. Lector priests recited spells that symbolically reunified the image of the dead as someone removed from life back into a single entity, a single “text” or “hieroglyph,” as Assmann puts it (33), enabled by the speech acts of the lector priests. When the purified body was fully prepared, it was transferred to its tomb. Here, the important Opening of the Mouth ritual was performed, which, again, reanimated the dead so that it could receive offerings and listen to the words of the mortuary rites that were recited over it. Once everything was performed properly for the dead, the deceased was no longer dead in a symbolic, religious, or even social way. Within these dimensions, death had been conquered.

We at the SCRC who work with the C-SPAN viewer mail deal with thousands of letters linked together only by the fact that they were sent to C-SPAN in the 80s and 90s. If I were a more cynical person, I’d say these are dead voices, lost to history apart from them being assigned to fading paper. This is where our symbolic role as lector priests becomes a little clearer. These letters all died as soon as they were placed into C-SPAN’s own archive, and remained so until C-SPAN asked the SCRC to help create a virtual archive of sorts to display the viewer mail. In other words, these letters were theoretically repurposed for this new project; thus, a new afterlife for these letters was born, but not yet populated. At the SCRC, we put this theory to practice; we reanimate the dead so they can enjoy this afterlife and so that these dead voices live on in a connected body, composed of many parts, but nevertheless a single entity. But how do we do so?

Like the Egyptians, we have an elaborate infrastructure in place to do this work, and, like them, each step of the long process is meticulously planned. After we receive the boxes of letters, we first compile metadata for categorical purposes. Once we have all the metadata for a respective box, we begin to digitize them, a process that involves going back through all of our boxes and taking pictures of each letter, which find their way into a vast digital archive. Eventually, we redact private information from these letters so that they’ll be ready for display on the C-SPAN project. Now, let’s once again think about this symbolically. Because these letters are all destined for a glorious afterlife, we need to prepare them beyond just the physical steps of purification. We need to breathe life back into them, to reanimate their voices. Digitizing, in my view, accomplishes this. We are the selfsame lector priests and share their same responsibilities. Our spells, though, are recited with a click of the camera. Think of digitization as a method of preservation in both a practical, professional capacity, but also within the realm of religious symbolism. We are saving the letters and their content from the foulness of death in the ancient Egyptian sense. We embalm not only individual letters, but, because they are all part of a single entity, a single “hieroglyph,” if you will, we embalm them together, as well. We’re linen-wrapping a purified body made up of THOUSANDS of letters that, without our involvement, would suffer the same fate as Ozymandias, left to occupy some meaningless spot in “the lone and level sands” of death. The dead voices in the letters, then, become voices that can ring out again, but only because we in the living world can and will engage with them.

This last point will be especially decided when the project is finally launched. At this point, though, we are still stitching together the body and (re)integrating and repurposing the letters into a recognizable social structure. The mummy is almost complete. When we do eventually “bury” it, we will make sure to Open its Mouth—we’ll allow it to be engaged with by doing this while simultaneously facilitating its chance at a happy afterlife in the form of the project. In this respect, people who will eventually go through the project will ensure the voices behind the letters will be heard, even if their names won’t be (due to the redaction). The Egyptians would be horrified by redaction, for somebody nameless can’t be remembered, and therefore would remain isolated from both the life-giving social and symbolic spheres that come with a rebellion against death. We don’t have that option, but you don’t really need a name to recognize the heart within a letter, or to compose a project of this nature. The end result—this singular entity—will remain, and it will be interacted with, whether by C-SPAN fans, doctoral students, or the average citizen. We here at the SCRC, then, aren’t killing the letters and letting their souls slip further into oblivion; in fact, we’re doing just the opposite. We’re letting them breathe and live again, and letting them survive outside of some dusty corner at the C-SPAN offices. Remember the idea that the “house of death is the house of life?” If we apply this to what we’re doing, this digital archive is indeed a tomb for the mummy, but one that we (and you, in time; just be patient!) can wander into and prolong the memory of this multi-faceted mummy.

Sources:

Assmann, Jan. 2005. Death and Salvation in Ancient Egypt, translated by David L. Lorton.

Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

David, Ann Rosalie. 2003. Mummification. In The Ancient Gods Speak: A Guide to Ancient

Egyptian Religion, edited by Donald B. Redford. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Follow SCRC on Social Media and look out for future posts on our Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter accounts. To search the collections held at Special Collections Research Center, go to our website and browse the finding aids by subject or title. You may also e-mail us at speccoll@gmu.edu or call 703-993-2220 if you would like to schedule an appointment, request materials, or if you have questions. Appointments are not necessary to request and view collections.