This post was written by Teo Rogers, Digitization Student Assistant for the C-SPAN records Digitization Project. Teo has worked in SCRC for the past two years and is now graduating with his Masters Degree in Folklore from George Mason University. Thank you for everything you’ve done for us, Teo!

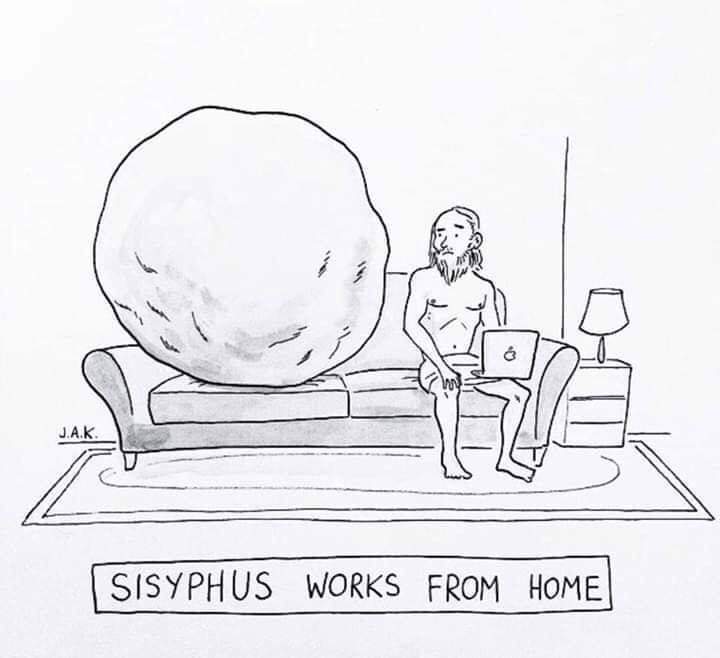

It’s hard to believe it’s been two years since I started working at the SCRC. I came here from a job in one of those hives of swarming illnesses that place your patience on a rack and stretch it so thin it’s almost two-dimensional: a preschool. Making the switch from holding tiny hands perpetually covered in snot and mud to an indoor office with clean-handed grown-ups was…appealing, to say the least. My first major role here was, as I covered in a previous blog post, to take on the almost Sisyphean task of compiling metadata from box after box, each of which contained letter after letter. I didn’t do it alone, though, not even remotely; in this case, Sisyphus had some friends to help push the boulder up the hill. Here we were, caught in a storm of historical and political discourse, with C-SPAN menacing at the center. How do you even begin to make sense of such an imposing beast?! In hindsight, with all of these boxes sorted (in every semantic sense), the situation maybe wasn’t so bad; it was way better than dealing with toddlers all day! At the time, though, a line from the Shel Silverstein poem “Long-Leg Lou & Short-Leg Sue” served as my kind of everyday mantra while trudging through letters: “And they take small steps and they do just fine.” Platitudinal it may be, but it helped a lot in both alleviating some anxieties about the project and in situating myself—not C-SPAN, not the letter—at the center of the struggle, in full control of it. Sisyphus took small steps, too, always encumbered by the boulder but not necessarily disheartened by his fate, that which “belonged to him,” as Albert Camus proposed. In keeping with Camus, “one must imagine Sisyphus happy” as he measured his struggle in small, toiling, joyous steps. When you’re inevitably glued to sifting through the final project, a consequence of finally pushing the boulder up the hill, remember that we’re doing just fine—and that we always were!

One of the more exciting individual days that I recall during my time at the SCRC was the day I met Brian Lamb. A nervous air pervaded the office; it was like an austere rock star or the Pope of cable T.V. was coming to visit. I was wearing a denim jacket covered in a veritable menagerie of enamel pins, and I bring that up only because I remember asking my supervisor if I should take it off in the presence of the Lamb (as I imagine his friends call him). I had a slightly less weird t-shirt on underneath, but I was assured it would be O.K. Still, I wasn’t sure what to expect. I had read so many letters directly about him, lambasting him for perceived political biases, praising him for his unparalleled interviewing skills or his impeccable taste in suits and ties, confessing smoldering physical attraction to him, and even poetry or cartoons dedicated to him. Here was the amorphous face and the persistent heartbeat of C-SPAN, a man who’d spoken to and matched wits with hundreds of heads of state and thousands of other important people. And I was going to meet him. Crazy.

My first impression of him was, ‘Damn, he does have an impeccable taste in suits and ties.’ My supervisor introduced us, and, as we shook hands, I thought to myself, ‘Damn if that’s not the firmest handshake ever.’ We chatted for a bit. Towards the end of our conversation, he asked me what letters I found the most interesting. Somewhat hesitantly, I told him about the tomes of correspondences that accused him of being too far left or right on the political spectrum, allegations gleaned from perceived unfriendliness to this conservative talk radio host or mocking smiles toward that liberal journalist. He sighed, gruffly—this was clearly not the first time he’d heard such complaints—and responded: “people see what they want to see.” The Lamb was as wise as an owl and as durable as the oak tree the owl was perched on; no words could hurt him, at least not on the surface. Soon enough, he walked away and I sat back down, back to my box of letters. It was a pretty cool experience, and best of all? He actually liked some of the pins on my jacket. So, Brian, if you’re reading this, hit me up if you want any recommendations for where to get some; they’ll make your suits even sharper, I guarantee it.

When enough of the metadata was harvested and stored away for the winter, I was moved to the photo lab, where I would begin my adventures in digitization. This process involves taking surgically precise pictures of…all the letters…we had been working on…for months. Sisyphus and Co. 2.0. The lab is also dark, as it needs to be for the sake of photography. There’s no need to fret, though. I won’t lie, digitization is a tedious job. But the routineness it affords is also incredibly, oddly soothing. It’s relaxing, and way less expensive than other means of leisure! Beyond the solace of mundanity, digitization is also fun in terms of what we do when we take pictures of the letters. Susan Sontag wrote of photography that its “most grandiose result…is to give us the sense that we can hold the whole world in our heads—as an anthology of images. To collect photographs is to collect the world.” At the lab, we were collecting the historical world of C-SPAN fan—and hate—mail, but we’re also projecting that compiled world into another world (the final project), serving an entirely different purpose than the initial anthologizing. We think this world into existence through photos but we create another one for the pictures to ultimately inhabit. So, there we are, in the darkness of the lab, populating worlds one letter at a time.

Like almost every office worker in the U.S., we at the SCRC were sent home in the middle of March 2020, as the pandemic began to ravage the country. I don’t think any of us were anticipating the outright stranglehold on time that such a shift placed on our working life; that was well over a year ago, and yet it still feels like only yesterday that all of us were working, maskless, in the same place. Some of us do go in now, but I’m not among that number. Anyway, my main responsibility at home was to work on redactions, removing names, street addresses, and the odd Social Security Number from digitized files. I’ve written about redacting in another post, so I won’t devote too much time to it here. Another job I had during my year-long work-from-home venture was to transcribe interviews with surviving members of the Federal Theatre Project (1935-1939), conducted in the 1970s and 1980s. This had nothing to do with the C-SPAN project, but I think there are some similarities as to the nature of both jobs. Transcribing interviews and oral histories, like working with photos, is an act of engaging with the past, in two layers. The first occurs during the interview itself; the interviewee’s life is interrogated and sequenced, memory by memory, into a kind of conversational anthology. Some cool ones I remember hearing include one woman’s journey in the development of the Puppetry Guild of Greater New York (which gave Jim Henson his start) and working with Orson Welles; one man’s story of a series of frozen nights spent protesting against efforts to dissolve theatre workers’ unions; and another man’s impressive resume of wardrobe designs for theatrical and cinematic productions. All of these stories are tinged in subtle hints of painful nostalgia, a walk down memory lane lined with shards of broken glass, while the interviewer nudges their subject along with questions and the eternal, whirring hum of the tape recorder.

Since we’re transcribing these interviews well after they were first recorded, though, the second layer of engagement swings squarely into our orbit. The interviews themselves are now pieces of history, and, like the harvesting of metadata from and the digitization of thousands of letters, to transcribe them for the purposes of a larger project creates a new world and a new life for these artifacts. This is the overarching effect of archival and museum work as a whole, to be fair. The only discernible difference, as I see it, is that we’re privileged enough to be able to hear (and capture) the voices on the interviews! This, however, doesn’t and hasn’t stopped me from sometimes reading the letters aloud, imagining the voices and intonations of their authors. (If you can’t tell from that sentence, I’ve been gradually losing my mind for some time.)

Working from home isn’t all bad. I get to hang out with my wife and our million pets. Wearing actual pants heralds a special occasion. I can’t help but feel robbed, though, of some of what made my time at the SCRC so fun. Gone were the delicious baked goods, the office-wide chats about Tolkien, the lectures opening up new exhibits, and the parties (of the Christmas and birthday variety), parties as lit as you can get in an archive. I laughed (watching Olive the Other Reindeer at said Christmas party), I cried (watching Olive the Other Reindeer at said Christmas party), and made good friends. For this last post, I wanted to provide some reflections of my specific tenure at the SCRC. As I sit here writing them, two weeks away from my last day, it is pretty sad to browse through my memories, from my first day to my looming last. Then again, memory functions as a cognitive archive, categorized in experience and filed in brimming folders. All I’ve done here is articulated some of them, or, better yet, selected a few of them to set out for display. But the rest are mine to keep.

Follow SCRC on Social Media and look out for future posts on our Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter accounts. To search the collections held at Special Collections Research Center, go to our website and browse the finding aids by subject or title. You may also e-mail us at speccoll@gmu.edu or call 703-993-2220 if you would like to schedule an appointment, request materials, or if you have questions.